Support for H-3 from Labor and Industry

Introduction

Government policies are wide ranging and can affect, for example, where mining activities can be conducted, how much fish can be caught in certain areas, and what quantity of pollutants can be emitted by industrial facilities. Unions, trade groups, businesses, and other entities that have a stake in outcomes of these decisions may try to influence policy by endorsing candidates whose priorities align with those of the organization, donating to committees advocating for a candidate’s election or a ballot measure’s passage or defeat, meeting with government officials, testifying in hearings, hiring lobbyists, litigating, and using media and other means to influence public opinion of candidates or of projects or policies.

Because there is potential for corruption and abuse, campaign finance laws, ethics laws, and lobbying laws at the federal, state, and county levels mandate transparency and regulate what entities can and can’t do. Many of these laws were enacted in the 1970s, in an effort to rebuild public trust in government following the Watergate scandal.

NOTE: The timeline events that have been categorized “support” represent the critical moments when freeway supporters mobilized the public through petition drives and letter-writing campaigns. Researchers should understand, however, that support was fundamentally woven into the basic effort to get H-3 approved and built. For example, although elections are not represented on the timeline, groups supporting the freeway helped to elect and re-elect leaders who were committed to completing the project.

Unions, trade associations, and businesses supporting H-3

The H-3 was supported by many Hawaiʻi unions, trade associations, construction firms and other businesses, who saw it as a creator of jobs and a boost for their industries. They exerted their influence through letter writing campaigns and petition drives, and by testifying, and voting for leaders and policies that supported their priorities. According to archives and newspaper clippings, the primary concentrations of activity occurred in 1973, to oppose the National Register of Historic Places designation for Moanalua Valley; and in 1985-1986, to support the 4(f) exemption.

Unions

Labor unions have a deep history in Hawaiʻi, from securing increases in wages and benefits for plantation workers and dockworkers, to mobilizing to help overturn Big Five dominance in the mid-20th century.[1] Organized labor remains a powerful political force in Hawaiʻi, which in 2022 had the highest rate of union membership–21.9%–of all U.S. states.[2]

Trade unions supported the freeway because according to them it would serve defense needs, create 2,500 direct and 7,500 indirect jobs, and relieve traffic congestion. Traffic was a particular concern, they contended. In a March 31, 1986, letter to U.S. Senator Stafford, United Steelworkers of America, District 38 president President Lionel K. Mathias wrote, “Jobs for workers are on the leeward side of Oahu. Many desirable homes are available for workers on the windward side of the island but they are not accessible due to the paralyzed conditions that exist between the leeward and windward coasts. Give us a break and cut through the Government red tape. Allow the H-3 Highway to be built so that leeward workers can commute to Windward Oahu without sitting for hours in traffic jams.”[3]

The Hawaiʻi State AFL-CIO supported the H-3,[4] as did the Plumbing and Mechanical Contractors Association of Hawai‘i – Plumbers & Fitters Local Union 675, the Hawaiʻi Building and Construction Trades Council, Operating Engineers Local Union No. 3, and United Steelworkers of America, District 38.[5]

Trade associations

According to the Federal Election Commission, a trade association is a group that is “organized to promote and improve business conditions in that line of commerce and not to engage in a regular business for profit.”[6]

The freeway was supported by influential Hawaiʻi trade associations, most of which (along with their Political Action Committees) are still active today. These included the Building Industry Association of Hawaiʻi, the Construction Industry Legislative Organization (a Honolulu-based organization that represented over 500 construction-related businesses), the General Contractors Association of Hawaiʻi, and the Chamber of Commerce Hawaiʻi.[7] In 1986, when the 4(f) exemption was moving through Congress, the General Contractors Association of Hawaiʻi organized a petition drive that collected 35,000 signatures. They also organized a letter writing campaign in which 15,000 individuals wrote to the chairs of the U.S. House and Senate committees responsible for considering the exemption, expressing their support for its passage.[8]

Other trade groups that wrote and testified in support of the freeway included the Architects and Engineers Corporation of America, Cement and Concrete Products Industry of Hawaiʻi, Consulting Engineers Council of Hawaiʻi, Hilo Contractorsʻ Association, Mason Contractors Association of Hawaiʻi, and the Oahu Contractors Association.[9]

Businesses

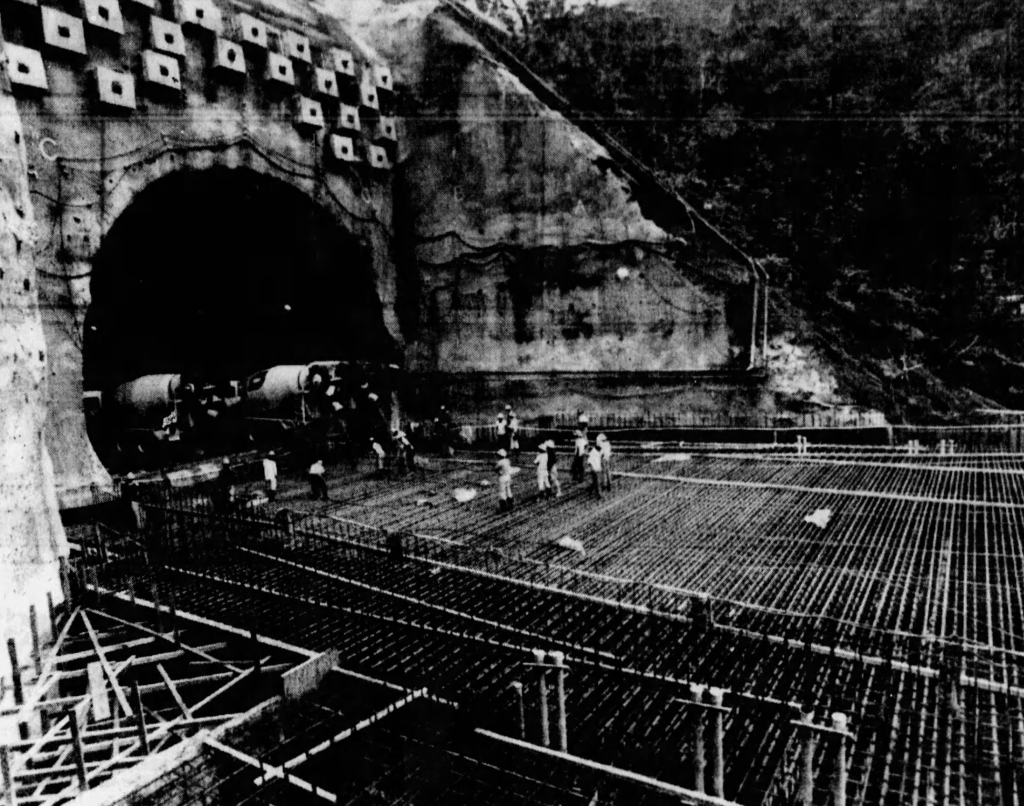

Unsurprisingly, construction-related businesses across Hawaiʻi also supported the freeway, which they saw as good for their firms and for their workers. The firm that was most active in lobbying in support of the H-3 was Dillingham Corporation/Hawaiian Dredging. Representatives for the company, along with Dillingham lobbyist Jack Ferguson, met with members of congress, and with state leaders and transportation officials. They wrote letters in support of the 4(f) waiver and, together with the Hawaiʻi Department of Transportation, in support of a public interest waiver from a temporary provision prohibiting foreign firms from bidding on federally funded construction contracts.[10] Hawaiian Dredging and H-3 Tunnelers (a joint venture of Hawaiian Dredging and the Obayashi Corporation) ultimately secured H-3 construction contracts in the amount of $272 million, second to Kiewit Pacific Co., which secured contracts in the amount of $809 million.[11]

Other construction industry businesses that wrote and testified in support of the freeway included Ameron/Honolulu Construction & Draying Co., Ltd.; Hawaiian Bitumuls and Paving Company, Limited; Hawaiian Cement; Hawaiian Western Steel Limited; and Pacific Machinery, Inc.

Distributors of food and beverages, livestock and poultry feed, and fuel also supported the H-3, stating that the H-3 would significantly reduce their delivery times and increase the safety of trans-Koʻolau transportation of products like gasoline and chemicals.[12]

Where to find information about how labor and industry affect political processes

Campaign finance disclosures

Campaign finance disclosures reveal which individuals and groups are supporting a candidate for elected office, or a particular ballot measure. In order to research campaign finances, it is important to understand the different types of entities involved.

A candidate committee is the authorized committee supporting a candidate for elected office. A candidate can have only one candidate committee. An example is Governor Green’s candidate committee, Josh Green for Hawaii.

A noncandidate committee is a committee that is created to support the election of a candidate or to support or defeat a ballot measure, but that is not the candidate’s authorized committee. An example of a standard noncandidate committee is the SHOPO Political Committee.

One type of noncandidate committee is the independent-expenditure-only committee, better known as the SuperPAC. Independent-expenditure-only committees can produce advertisements and other communications that advocate for or against a candidate or ballot measure, but they can’t be made in coordination with that candidate. In addition, independent-expenditure-only committees are no longer subject to contribution limits, which means they can raise unlimited amounts of money. An example of an independent expenditure committee is Be Change Now, the SuperPAC of the Hawaiʻi Regional Council of Carpenters, which, in the 2022 election cycle, spent over $2 million supporting Ikaika Anderson’s campaign for Lieutenant Governor.[13]

Note: The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission lifted prohibitions on unions and corporations making campaign contributions from their treasury funds. A related U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia decision, in SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission, held that the amount of money donated to independent-expenditure-only committees, or SuperPACS, could not be constitutionally limited.[14] These decisions potentially enable a small number of well financed individuals and special interests to raise unlimited money to support or defeat a candidate, as long as they are not doing so in coordination with the candidate. Though these decisions came long after the H-3 opened, they have significant impact on political processes today.

Federal elections

The Federal Election Commission is an independent (not part of the executive branch) regulatory agency established in 1974 to administer and enforce federal campaign finance laws. Its website, www.fec.gov, hosts extensive documents and data, including information about candidate committees and PACs; summaries of committee expenditures, contributions received, and loans; and lists of donors and donation amounts, sometimes going back as early as the 1970s.

State and county elections

The Hawaiʻi Campaign Spending Commission was established in 1973 by the state legislature to protect the integrity of the political campaign process, to make campaign spending data accessible, and to administer the public financing program. On the Campaign Spending Commissionʻs website, you can find data including contributions received, expenses, loans, and organizational reports from the 2008 election onward.[15] The website also hosts fundraising notices and data dashboards summarizing, for example, the top 10 PACs contributing to Hawaiʻi candidate committees.

Searchable data for candidate committees

Searchable data for noncandidate committees

Lobbyist disclosures

Federal and state law differ slightly in their definitions of a lobbyist. Common characteristics of both definitions are: an individual who is compensated in excess of a certain dollar amount for lobbying activities, and who spends a certain percentage of their time on lobbying activities.[16] Lobbyists may be engaged by their clients to influence legislation, to influence the administration and enforcement of rules and regulations, and to influence the implementation of government programs. Lobbyists may also be engaged to influence nominations and confirmations.

It is important for ordinary citizens to be able to petition their government, and to have access to elected officials. However, it undermines public confidence in government when well-funded and politically savvy special interests gain too much control–or are perceived to have gained too much control–over government decision making. Mandated lobbyist disclosures increase transparency.[17]

Federal disclosures

The Lobbying Disclosure Act of 1995 and subsequent legislation applies to members of congress and the President, the Vice President, and certain other executive branch officials.

U.S. Senate lobbying disclosures are maintained by the Secretary of the Senate and are searchable going back to 1999 here.

U.S. House lobbying disclosures are maintained by the Clerk of the House and are searchable, going back to 2000, here.

State disclosures

The Hawaiʻi State Ethics Commission administers and enforces the state ethics code (HRS 84) and lobbying law (HRS 97). On the state ethics commission’s data portal, you can find lobbyist registrations going back to 2019, as well as public financial disclosures and gift/travel disclosures for high ranking government officials, and, in election years, for candidates for elected office.

During the 2023 legislative session, several measures became law that were aimed at increasing transparency with regard to lobbying. These include a measure requiring the State Ethics Commission to establish and administer a mandatory lobbyist training course, a measure requiring state legislators to disclose relationships with lobbyists, and a measure preventing lobbyists from making campaign contributions before, during, and after the legislative session.

City and County disclosures

On the city and county level, ethics and lobbying laws are administered and enforced by the respective ethics commissions and boards:

- Honolulu Ethics Commission

- County of Maui Board of Ethics

- County of Hawaiʻi Boards and Commissions (including Board of Ethics)

- County of Kauaʻi Lobbyist Registration

Archives

The Hawaiʻi Congressional Papers Collection at the UH Mānoa Library

The Center for Labor Education and Research (CLEAR) at the University of Hawaiʻi at West Oʻahu

Notes

- Center for Labor Education and Research, University of Hawaiʻi West Oʻahu, “CLEAR Guide to Hawaiʻi Labor History,” at http://www.hawaii.edu/uhwo/clear/home/pdf/CLEAR_Hawaii_Labor_Hist_Pamphlet_2018.pdf. ↑

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, “Hawaii Had the Highest Rate of Union Membership in 2022,” The Economics Daily, at https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2023/hawaii-had-the-highest-rate-of-union-membership-in-2022.htm. ↑

- James L.K. Tom to Senator Inouye, April 3, 1986, box LF119 folder 9, Daniel K. Inouye Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library; Lionel K. Mathias to Senator Stafford, March 31, 1986, box LF119 folder 9, Daniel K. Inouye Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library. ↑

- “Kupau asks Fong Help on H-3,” Honolulu Advertiser, March 15, 1972; George West, “3 Groups Come Out for the H-3,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, February 13, 1974. ↑

- Box 155, folders 6-10, Hiram Leong Fong Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library; Box 404, folders 8-14, Spark M. Matsunaga Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library; Box LF119 folder 9, Daniel K. Inouye Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library. ↑

- Federal Election Commission, United States of America, at https://www.fec.gov/. ↑

- Box 155, folders 6-10, Hiram Leong Fong Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library; Box 404, folders 8-14, Spark M. Matsunaga Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library; Box LF119 folder 9, Daniel K. Inouye Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library. ↑

- James L.K. Tom to Senator Inouye, April 3, 1986, box LF119 folder 9, Daniel K. Inouye Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library. ↑

- Box 155, folders 6-10, Hiram Leong Fong Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library; Box 404, folders 8-14, Spark M. Matsunaga Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library; Box LF119 folder 9, Daniel K. Inouye Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library. ↑

- Box 404, folders 8-14, Spark M. Matsunaga Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library; Box LF119 folder 9, Daniel K. Inouye Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library. ↑

- Mike Yuen, “Open Road: The Money,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 3, 1997. ↑

- Box LF119 folders 9 and 11, Box LF121 folder 5, Daniel K. Inouye Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library. ↑

- Blaze Lovell, “This Hawaii Super PAC is Spending Millions to Defeat One Political Opponent This Year,” Honolulu Civil Beat, August 5, 2022. ↑

- U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Campaign Finance: Key Policy and Constitutional Issues, IF 11034 (Updated December 3, 2018); U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, The State of Campaign Finance Policy: Recent Developments and Issues for Congress, R4152 (Updated September 7, 2023). ↑

- The commission is only required to retain campaign spending data for the most recent 10 years. ↑

- U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, The Lobbying Disclosure Act at 20: Analysis and Issues for Congress, R44292 (Updated December 1, 2015), Haw. Rev. Stat. Chapter 97. ↑

- U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, The Lobbying Disclosure Act at 20: Analysis and Issues for Congress, R44292 (Updated December 1, 2015). ↑