Regulatory Compliance Processes

Introduction

Federal, state, and local regulatory agencies write regulations, or administrative rules, that correspond to laws passed by a legislative body. These regulations set out requirements for compliance with laws that govern transportation funding, protection of the environment, urban planning, and historic preservation, among others. For example, Congress passed a law called the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1969 that requires federal agencies to consider environmental impacts in their decision making. The federal Council on Environmental Quality then issued regulations that state how federal agencies are required to comply with NEPA.

During the planning and construction of H-3, several federal and state regulatory processes influenced how government agencies went about their work. In particular, the environmental review process, historic preservation regulations, U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) funding requirements, and planning and zoning regulations had bearing on the actions of government agencies. These regulations also formed the basis of some of the litigation related to H-3, when opponents argued that the state or federal government had not complied with laws or regulations.

An important thing to remember about regulatory processes is that they all provide opportunities for direct public input into the creation or amendment of regulations and proposed projects that must comply with regulations.

Federal Transportation Funding

To receive funding from USDOT for the planning, land acquisition, and construction of H-3, the state had to comply with Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) regulations. The regulations specify the kinds of planning activities a state must engage in and the construction standards that the state must adhere to. Lack of unity between city and state proved to be a persistent challenge to the H-3 project. In order to qualify for federal funding for transportation projects, the city and state needed to show the federal government that they were coordinating on transportation planning.[1] In 1968, the city and state created the Oahu Transportation Planning Program (OTPP) to approve all transportation projects as a prerequisite to receiving federal funding.[2] In 1975, however, the four-member OTPP was decertified by the federal government because city representatives and state representatives could not agree on which projects should be funded.[3] The Oʻahu Metropolitan Planning Organization (OMPO) was created to replace OTPP later that year. Consisting of ten state legislators and the nine-member Honolulu City Council, the OMPO Policy Committee represented a renewed attempt at city-state coordination on transportation planning.[4]

The federal government gave Hawaiʻi a deadline of September 30, 1986, to either commit to finishing H-3 (and risk losing all $716 million in federal funds if the project could not overcome legal challenges that had stalled construction), or to transfer the federal funds to other transportation projects, like mass transit. If the state wanted to transfer the funds, the OMPO, the governor, and the mayor needed to agree on potential alternative projects and notify FHWA.[5] At the same time, a controversial environmental exemption that would have allowed the stalled work on the freeway to resume was making its way through Congress. When passage of the congressional exemption was assured, Governor Ariyoshi allowed the September 30 transfer deadline to pass, thus committing the state to the completion of H-3.[6]

Other federal highway funding laws and regulations relate to design and public input. For example, Section 4(f) of the Transportation Act of 1966 requires parks, recreation land, wildlife refuges, and historic sites to be considered during transportation project development. This section of the law became a very contentious issue in the planning of H-3. In 1974, Judge King ruled that the project did not require a 4(f) statement. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned his ruling and required a 4(f) statement. However, when the site was changed from Moanalua to Hālawa, the issue arose again. This time, Judge King ruled that a 4(f) statement was required due to the route’s proximity to Hoʻomaluhia Park. The state argued that H-3 had been designed in conjunction with a flood control project that resulted in the creation of Hoʻomaluhia Park. Because the freeway design was coordinated with the park development, the state contended that the freeway did not require a 4(f) statement.[7] In a later court case that aggregated many complaints, the Ninth Circuit ruled that the requirements of section 4(f) had not been satisfied. This ruling triggered a move by Hawaiʻi’s congressional delegation to introduce a bill to exempt the project from the requirements of Section 4(f). The bill became law and survived a legal challenge to the US Supreme Court, thus enabling construction of H-3 to proceed.

Environmental Review Process

National Environmental Policy Act

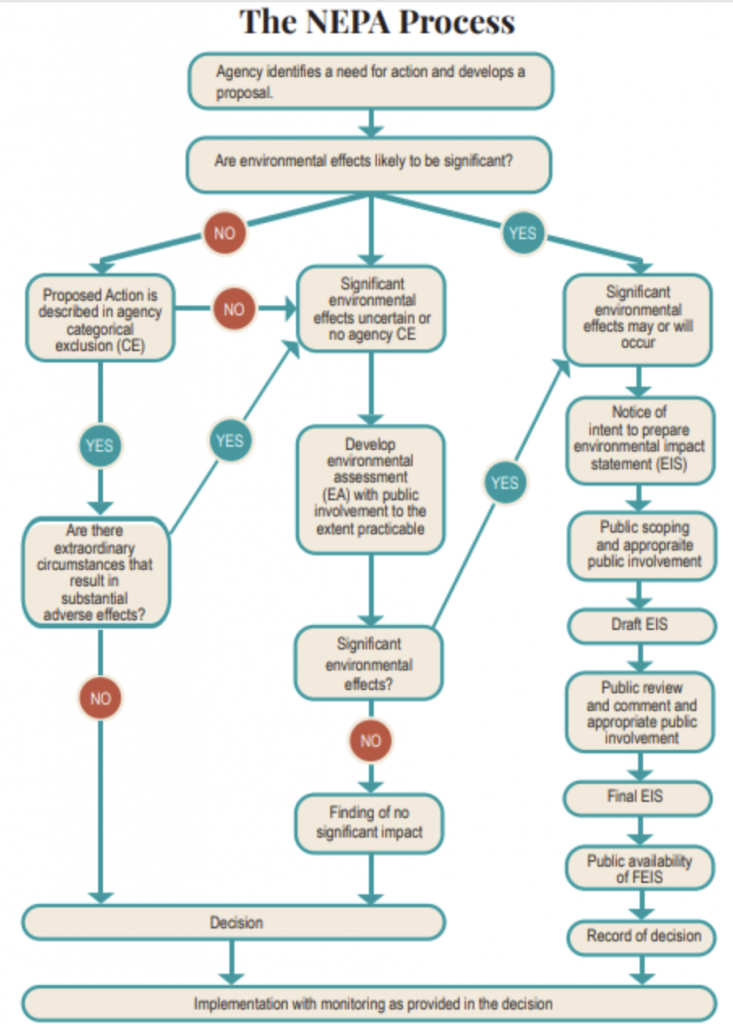

The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 requires federal agencies to conduct environmental reviews to determine whether a proposed federal action may have significant environmental effects. Federal actions can include things like construction projects or the issuance of permits for activities such as grazing or mining. Regulations (40 CFR 1502) govern the EIS process. Each agency maintains a list of actions that can be “categorically excluded” from the EIS process, used when an agency determines that a proposed action does not have a significant effect on the environment. If an action is not excluded, the federal agency may then prepare a draft Environmental Assessment (EA). If the agency determines that the action will not have significant environmental impacts, it will issue a final EA and Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI). If the agency determines that the environmental impacts of a proposed action will be significant, it prepares a draft EIS (DEIS).

EAs and EISs are usually written by third-party contractors who have subject matter expertise. An EIS consists of a description of the parcel of land, maps, photographs, and information about the site’s environmental conditions, geology, land use, archaeological sites, history, and social and economic significance. The EIS also contains a description of the proposed action, its anticipated impacts, and alternatives considered. The agency announces the notice of intent to prepare an EIS and the availability of the EIS in the Federal Register, which is the daily journal of the United States government.

Members of the public may review and comment on the DEIS. Comments received may be posted on the agency’s website. An agency may revise the DEIS in response to comments received. In that case, the agency may prepare a final EIS (FEIS) and issue a Record of Decision (ROD). An agency may revise an EIS or complete a draft supplemental EIS if the scope of the project changes or if new information is received. Revised and supplemental EISs go through the same public comment process as the original EIS. Opponents of an agency’s proposed action may file suit to raise objections to the conduct of the EIS process or the conclusions reached in the EIS. Legal action may also be taken to force an agency to complete an EIS when the agency has determined that one is not required. In such cases, a judge may order the agency to complete or redo an EIS.

A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA explains the federal environmental review process.

[Insert graphic based on flow chart on page 8 of A Citizen’s Guide to the NEPA]

State Environmental Review Laws

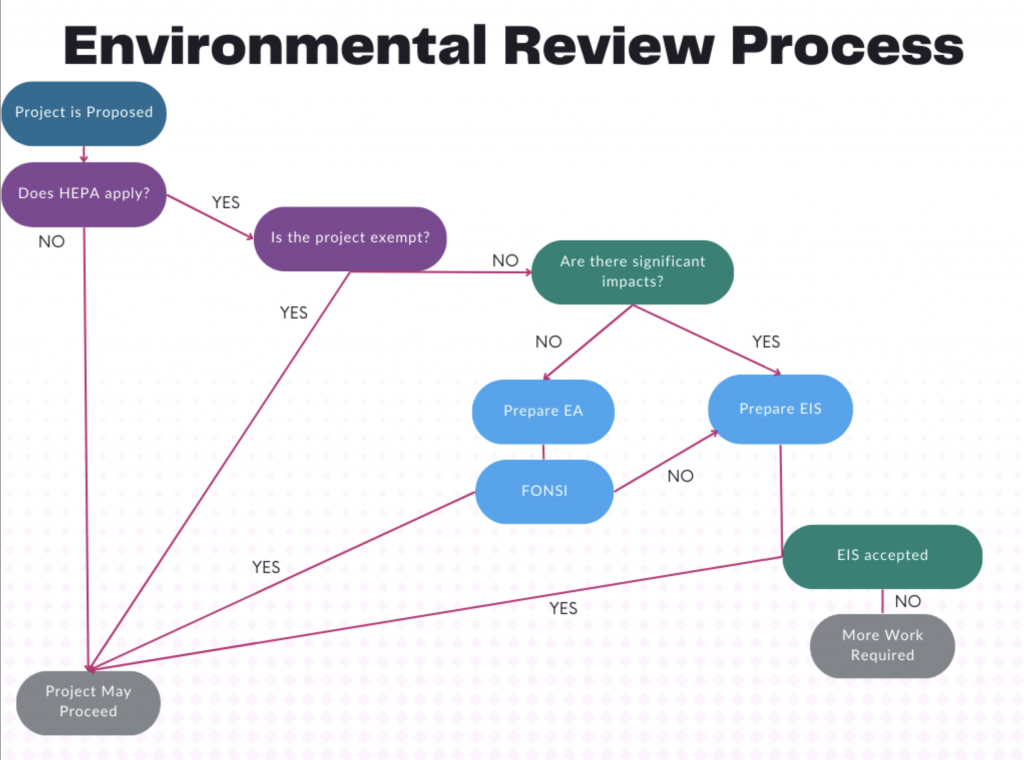

Some states have laws that require environmental assessments for projects regulated by the state. For example, the State of Hawaiʻi’s Environmental Review Program enforces the Hawaiʻi Environmental Policy Act. It requires a review process similar to the federal process described above. More information can be found in the Hawaiʻi Environmental Policy Act Citizen’s Guide. The federal government and state governments can and do cooperate in the preparation of EISs that cover the requirements of both the federal and state laws.

[Insert graphic based on the flow chart on page 3 of Hawaiʻi Environmental Policy Act Citizen’s Guide]

Where to Locate EISs and EAs

- Recent federal EISs and related documents may be found on the website of the agency that issued the documents.

- Older federal EISs and associated comments may be available in the EPA’s EIS Database, which covers 2012-present, but does not include EAs.

- The Northwestern University Transportation Library’s database is the most comprehensive collection of federal EISs but it does not include EAs.

- The Defense Technical Information Center includes federal EISs and EAs for military sites.

- The HathiTrust database contains many federal EISs and EAs.

- Google Books includes many federal EISs and EAs.

- Hawaiʻi state EISs are in the Environmental Review Program’s online library of EISs and EAs.

- The Hawaiʻi State Library maintains a collection of printed and microform state and federal EISs and EAs for Hawaiʻi projects.

- Local libraries may have copies of state and federal EISs for projects in the library’s service area.

The H-3 EIS Process

Draft EIS1

Initially, the state commenced construction without preparing an EIS. However, U.S. Secretary of Transportation John Volpe ordered a halt to construction and directed the state to prepare an EIS. The State Highways Division completed a DEIS in June 1971 for the Moanalua alignment. As EISs go, it is very brief. It includes the following analyses:

- Historical narrative

- General environmental impacts

- Visual impact and aesthetics

- Noise impacts

- Air pollution studies

- Displacement of families

- Business and employment

- Agriculture

- Schools and religious institutions

- Public recreational facilities

- Historical and natural features

- Mass transportation

- Unavoidable adverse environmental impacts

- Alternatives

- Relationship between local short-term environmental uses and maintenance and enhancement of long-term productivity

- Irreversible and irretrievable commitments of resources

- Corridor study map

- Route map

- Distribution list, which lists many government and private organizations to which the draft was distributed.

- An appendix, which contains comments on the draft, responses of the State Highways Division to the comments, and letters about H-3 in general that are not comments on the DEIS.

The initial EIS of June, 1971 was not accepted by the FHWA, being deemed inadequate.

“Pre-Final” EIS2

A second, final [the cover is overstamped with the words “Pre-Final”] EIS was also rejected by the FHWA. The Pre-Final EIS, dated October 1971, includes appendices as follows: [Volume 1 not available at UHM Library or HSL; maybe they simply attached the appendices to the draft and called it “final”?]

- Appendix 2(a). Letters requiring response

- Appendix 2(b). Letters requiring no response

- Appendix 2(c). Other comments from organizations

- Appendix 3. Authors’ biographical data

- Appendix 4(a). Acoustics study

- Appendix 4(b). Emissions and air pollution study

- Appendix 4(c). Botanical study.

- Appendix 4(d). Wildlife study

- Appendix 4(e). Archaeological studies

- Appendix 4(f). Mass-transit diversion study

- Appendix 4(g). Water supply study

- Appendix 4(h). Stream flow and siltation study

- Appendix 4(i). Meteorological study

Final EIS3

In August 1972 the Final EIS was issued by the state and it was accepted by the FHWA in May 1973.

Volume II https://hdl.handle.net/2027/ien.35556030122261

Preface Appendix A: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/ien.35556030122337

Draft Supplemental EIS, 19774

Due to court rulings, the Moanalua alignment of H-3 was abandoned. The FHWA prepared a Draft Supplemental EIS for the Halawa alignment in 1977. It contains the following sections:

- Introduction, including the legal authorities for the project and a history of the project

- A description of the proposed project, describing the need for H-3, alternatives, costs, schedule, use of public lands

- Environmental setting: the regional setting; the topography, soils, weather, air quality, noise levels, flora, fauna, history and archaeology, aesthetics and recreation, land tenure and public facilities, population and housing, transportation, land use and development, and tax base and income

- Relationship of the proposed Halawa alignment to state plans, goals, objectives, and policies

Final supplemental EIS, 19805

The U.S. Department of Transportation completed the final supplemental EIS in 1980 and it was accepted by the FHWA. It contains the following sections:

Volume 1.

- Introduction

- Description of the proposed action

- Environmental setting of the proposed action

- Relationship of the revised H-3 alignment to land development plans, policies, controls, goals, and objectives

- Probable environmental impact of the proposed action

- Probable adverse environmental impacts which cannot be avoided should the proposed action be implemented

- Alternatives to the proposed action

- Relationship between local short-term uses of man’s environment and the maintenance and enhancement of long-term productivity

- Irreversible and irretrievable commitments of resources

- Coordination, comments and responses

Technical appendices

- Volume 2. Plans of the proposed interstate route H-3 alternatives

- Volume 3.

- Appendix A. H-3 and the transportation planning process.

- Appendix B. Interstate Route H-3 alternatives study – Travel Demand Analysis

- Volume 4.

- Appendix C. Technical report on air quality conditions and impacts of the North Halawa alignment of Interstate Route H-3.

- Appendix D. Technical report on noise conditions and impacts of the North Halawa Alignment of Interstate Route H-3.

- Appendix E. Energy impact analysis of the North Halawa Alignment of Interstate Route H-3.

- Volume 5.

- Appendix F. Report on the vegetation and flora of North Halawa Valley, Oahu.

- Appendix G. Avifaunal Survey of North Halawa Valley, Oahu.

- Appendix H. Archaeological Phase I survey of the leeward Portion of Proposed Interstate H-3, North Halawa Valley, Oahu. Archaeological Phase I survey of the windward Portion of Proposed Interstate H-3: Halekou Interchange to Windward Portal of Koolau Tunnel, Oahu.

- Volume 6.

- Appendix I. Supplemental study – Interstate Route H-3 alternatives – Island-wide travel demand analysis.

- Appendix J. Island-wide air quality analysis. Appendix K. Avifaunal survey in the central Koolau Range, Oahu.

- Appendix L. Trans-Koolau North Halawa transportation corridor – noise contour analysis. Appendix M. Collocation factors – H-3 and OMEGA station – Haiku – December 4, 1978, Report no. 234 and collocation study – H-3 and OMEGA station Haiku –Phase II – May 9, 1979, report no. 236.

- Volume 7.

- Written and public hearing comments on interstate route H03 supplement to the E.I.S. with responses.

Second Supplemental EIS, 19826

In 1982, the U.S. District Court ruled that a second supplemental EIS was required to address the new and significant information from the H-3 Omega Collocation Studies, Federal Highway Administration Region Nine Staff Analysis, and Hoʻomaluhia Botanical Garden 4(f) statement. The U.S. Department of Transportation, FHWA, and State of Hawaii Department of Transportation jointly prepared the second supplemental EIS. It was approved in 1982. All of the documents that were addressed in the first supplemental EIS are reproduced in their entirety in the second supplemental EIS.

Contents:

- Introduction

- Purpose and need

- Alternatives including proposed action

- Proposed action

- Other alternatives

- Affected environment

- Environmental consequences

- General

- H-3/Haiku-OMEGA collocation

- Relationship of proposed action to Section 4(f) lands

- Introduction

- Hoomaluhia Park

- Pali Golf Course

- Comments and coordination

- List of preparers

- Special studies

- Comments on the EIS preparation notice [contained in the draft second supplement environmental/4(f) statement (1982)]

- Comments on Draft Second Supplement

- Public Hearing Testimony and Evaluation

Third Supplemental EIS, 19877

The Third Supplemental EIS was required because, due to court injunctions, no work had been done on H-3 since 1983. FHWA regulations required that a reevaluation be prepared before work could recommence. The Third Supplemental EIS discusses archaeological mitigation plans for Kāneʻohe Interchange design alternatives A and B and their impacts on the Luluku Discontiguous Archaeological District.

Contents:

- Project background

- Purpose and need

- Proposed action including alternatives

- Proposed action

- H-3 alignment

- Kaneohe Interchange alternatives

- Recommended alternative

- Cost and schedule

- Other alternatives considered

- Proposed action

- Affected environment

- General

- Luluku Discontiguous Archaeological District

- Environmental consequences

- Rights-of-way and relocation impacts

- Prime and unique agricultural lands

- Visual impacts

- Air quality

- Noise

- Historical and archaeological impacts

- The relationship between local short-term uses of man’s environment and the maintenance and enhancement of long-term productivity

- Unavoidable impacts and irreversible and irretrievable commitments of resources

- Coordination

- EIS preparation notice mailing list of agencies, organizations, and persons (state EIS regulations)

- DTSEIS mailing list and respondents

- Public hearing/section 106 informational meeting

- List of preparers

- References

Historic Preservation Laws and Regulations

Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act

One of the best known historic preservation laws is the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Passed in 1990, NAGPRA acknowledges that human remains and other cultural items belong to lineal descendants, Native American tribes, or Native Hawaiian organizations. NAGPRA and associated regulations are administered by the National Park Service (NPS) and govern the actions of federal, state, and local governments as well as universities and museums. However, because NAGPRA was not passed until 1990, it was not a governing factor in the planning and construction of H-3.

Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979

The Archaeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA) was enacted to protect archaeological resources on public lands. It defines archaeological resources, establishes standards for archaeological investigations, prohibits the public disclosure of sensitive information regarding archaeological resources, and requires the sharing of information between agencies.

National Historic Preservation Act

The National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) of 1966 created the National Register of Historic Places, an official listing of sites deemed worthy of preservation. The NHPA, which the National Park Service enforces, provides that the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation must be given an opportunity to comment on federal agencies’ projects on listed properties. In 1973, Pohaku ka Luahine and other pre-colonial Hawaiian cultural sites of Moanalua were added to the National Register, thus confirming the unsuitability of Moanalua as a route for H-3.

Additions of properties to the National Register are announced in the Federal Register, the federal government’s daily news journal. A database of National Register properties is available on the NPS website. Some of the nomination documents have been digitized. Some National Register documents are available online in Record Group 79, Records of the National Park Service, on the National Archives and Records Administration website. However, access to sensitive documents, including those related to Pohaku ka Luahine, is restricted due to ARPA.

Hawaiʻi State Laws and Regulations

State Historic Preservation Division

Established in 1976, the Hawaiʻi State Historic Preservation Division (SHPD), part of the Department of Land and Natural Resources, administers state laws regarding historic preservation, including Chapter 6E (Historic Preservation) of Hawaii Revised Statutes (HRS). SHPD administrative rules specify the standards for archaeological reviews, professional qualifications of archaeologists, permitting procedures for archaeological excavations, handling of human remains, site preservation, and other aspects of historic preservation.

- The Hawai‘i Historic Places Review Board under SHPD votes on the listing of the nominated properties to the Hawai‘i Register and recommends nominations for the National Register of Historic Places. SHPD maintains a list of Hawai‘i state register and national register sites.

- The Archaeology Branch of SHPD reviews federal, state and local projects with potential impacts to historic properties under HRS 6E and Section 106 of NHPA.

- The Architecture Branch of SHPD reviews federal, state and local projects for impacts to Hawai‘i’s historic places.

- The SHPD History and Culture Branch oversees the management of burial sites over 50 years old and works with five burial councils regarding Native Hawaiian burials.

- SHPD reports, surveys, and other documentation are available in the SHPD Library. Some are described in the Papakilo database, which is maintained by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs. Be aware that many reports contain sensitive information and are therefore not available for viewing.

Planning and Zoning

State Land Use Commission

Chapter 205 of Hawaiʻi Revised Statutes established the State Land Use Law, a framework that classifies all lands in the state into one of four land use districts: urban, rural, agricultural, or conservation. The Land Use Commission (LUC) is the body that administers the statewide land use law. It establishes the district boundaries for the state and makes decisions on petitions for boundary changes submitted by private landowners, developers, and state and county agencies. The LUC also approves or disapproves special use permits within the Agricultural and Rural Districts. LUC’s decision-making process is “quasi-judicial,” meaning that the individuals and organizations most affected by a decision are “parties” to the proceedings. Individuals or organizations whose interests are distinct from the general public’s interest may also petition to be added to the proceeding as an intervenor. Declaratory orders, minutes, and some transcripts of the LUC’s proceedings are available on its website.

State Conservation Districts

The Legislature designates conservation districts (CDs) in state law to protect open space, recreation, aesthetic, historic and cultural values, critical wildlife habitat, and watershed areas. A Conservation District Use Permit (CDUP) is required to conduct certain activities on lands that are in a CD. Administrative rules specify the different types of conservation districts and permits. The party requesting a CDUP must submit a Conservation District Use Application (CDUA) to the Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR). Depending on the type of land use, either DLNR or the Board of Land and Natural Resources (BLNR) has the authority to approve the CDUA. Upon approval, DLNR or BLNR issues a CDUP. Individuals who wish to view a CDUA or CDUP must make a request to DLNR through a Uniform Information Practices Act (UIPA) form, Request to Access a Government Form. BLNR meeting minutes are available on the DLNR website.

In 1975, BLNR granted a CDUP for H-3 to cross conservation lands in Moanalua and Haʻikū Valley. In 1981, the Hawaiʻi Department of Transportation petitioned the state Board of Land and Natural Resources (BLNR) for an amendment to the 1975 CDUP to address the realigned route through North Hālawa Valley. BLNR subsequently granted the amended permit.

County Planning

Counties create islandwide or regional general and development plans to guide development, zoning, and land use. The Honolulu City Council first adopted the Oʻahu General Plan in 1964. The most recent General Plan was approved in 2022. Individuals or organizations may submit an application for an amendment to the plan to the Honolulu Department of Planning and Permitting (DPP). DPP rules determine how the department handles proposed amendments. DPP reviews each application to determine whether it is acceptable, i.e., whether it identifies a legitimate issue that must be changed in the general plan. DPP solicits public comment on amendments it deems acceptable and then forwards the amendments to the Honolulu Planning Commission, which holds a public hearing on the proposed amendment(s). The Planning Commission submits its findings and recommendations to the City Council, which takes a vote on a resolution to adopt the amendment(s). Honolulu City Council minutes and resolutions are available on the City Clerk’s website.

In the case of H-3, the State Department of Transportation acknowledged in 1972 that an amendment to the Oʻahu General Plan was required for construction of H-3 because the freeway was not mentioned anywhere in the plan. Opponents of H-3 argued that this omission meant that it was not legal to construct the freeway. In May 1974, the Honolulu City Council voted to add the H-3 freeway to the Oʻahu General Plan.

Notes

1 U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration and State Highways Division, Department of Transportation, State of Hawaii, Environmental Impact Statement for Interstate Route H-3 : Halawa Interchange to Halekou Interchange, Oahu, Hawaii (Honolulu: Honolulu: State of Hawaii Highways Division, 1971).

2 State of Hawaii, State Highways Division, Department of Transportation, Final [overstamped “pre-final”] Environmental Statement, Administrative Action for Interstate Route H-3, Halawa Interchange to Halekou Interchange, Oahu, Hawaii (Honolulu: Federal Highway Administration, 1971).

3 U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration and State Highways Division, Department of Transportation, State of Hawaii, Final Environmental Statement, Administrative Action for Interstate Route H-3, Halawa Interchange to Halekou Interchange, Oahu, Hawaii (Honolulu: State of Hawaii Highways Division, 1972).

4 U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration and State of Hawaii Department of Transportation, Interstate Route H-3, Halawa Interchange to Halekou Interchange, City and County of Honolulu (Honolulu: Federal Highway Administration, 1977).

5 U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration and State of Hawaii Department of Transportation, Interstate Route H-3, Halawa Interchange to Halekou Interchange, City and County of Honolulu, Oahu, Hawaii: Administrative Action: Final Supplement to the Interstate Route H-3 Environmental Impact Statement (Honolulu: Federal Highway Administration, 1978).

6 State of Hawaii Department of Transportation, Interstate Route H-3, Halawa Interchange to Halekou Interchange, City and County of Honolulu, Hawaii : Final Second Supplement Environmental Impact/4(f) Statement (Washington, D.C: Federal Highway Administration, 1982).

7 U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration and State of Hawaii Department of Transportation, Interstate Route H-3 Halawa to Halekou Interchange : Final Third Supplement to the Interstate Route H-3, Environmental Impact Statement (Washington, D.C.: Federal Highway Administration, 1987).

Public Document Requests

Both federal and state laws provide for citizens to request copies of documents from government agencies. The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) sets out the process that federal agencies in the executive branch must follow when they respond to requests for documents. A different law, the Presidential Records Act, governs the availability of presidential documents, but FOIA covers the request process. Neither of these laws applies to Congress, however, which has argued that due to the “speech or debate” clause in the US Constitution, it is not required to make its internal documents publicly available. Similarly, the judicial branch is protected from public disclosure of its internal deliberations. Agencies are permitted to charge fees for copies of documents. There are many exemptions to FOIA that may enable agencies to deny some FOIA requests.

In Hawaiʻi, the Uniform Information Practices Act (UIPA) is similar to FOIA. Members of the public must use the Request to Access a Government Form to request documents from executive branch agencies. Just as FOIA only applies to the executive branch of the federal government, UIPA only applies to the executive branch of the state government.

-

“The federal requirement for transportation planning in urban areas, although not MPOs [metropolitan planning organizations], dates to the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1962 (P.L. 87-866), which called for “a continuing comprehensive transportation planning process carried on cooperatively by states and local communities.” MPOs themselves have been required as part of the transportation planning process in urbanized areas since the enactment of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1973 (P.L. 93-87) (23 U.S.C. §134; 49 U.S.C. §5303).” U.S. Library of Congress, Congressional Research Service, Metropolitan Transportation Planning, R41068 (2010). ↑

-

David Smollar, “City Transit Rule Urged,” Honolulu Advertiser, January 30, 1975. ↑

-

Dianne Armstrong, “Sacrifices Federal Aid: Fasi Balks on Transit Program,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, August 22, 1975. ↑

-

Ibid.; “OMPO’s Good Beginning” (editorial), Honolulu Advertiser, July 19, 1975. ↑

-

Peter Wagner, “Inouye: No Need to Hurry with H-3 Transfer,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, August 28, 1986. ↑

-

Floyd K. Takeuchi, “Ariyoshi Bets It All on H-3, Lets Deadline Pass,” Honolulu Advertiser, October 1, 1986. ↑

-

State of Hawaii Department of Transportation, H-3 Fact Sheet, September 1985, Daniel K. Inouye Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Library. ↑