Opposition to the Freeway

The movements of opposition against the construction of the H-3 freeway drew from diverse groups of local, newcomer, and Kānaka Maoli peoples’ insistence on the historical, cultural, and environmental significance of Moanalua, Kāneʻohe, and Hālawa valleys. The H-3 interstate freeway was created as part of a U.S. defense highway system to connect military bases, Pearl Harbor and Kāneʻohe Marine Corps Base, on the island of Oʻahu. There were concerns about the implications of the freeway increasing military use of lands, and the impact of over-development on the island’s ecosystem and its peoples. This freeway was one among many freeways constructed as part of the 1959 Act to Provide for the Admission of the State of Hawaiʻi into the Union.

This essay analyzes select archival materials documenting the opposition to the H-3 freeway from these collections:

- The University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library H-3 Litigation Archive

- The Center for Oral History Social Movements in Hawaii Ethnic Studies Resources Collection on the Opposition to H-3

- Hawaiʻi Peace and Justice Archives (formerly American-Friends Services Committee)

- Marion Kelly Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Hamilton Library Archives

These collections are not the only sources on the opposition to the H-3. But this set of collections documented a mixture of opposition strategies and tactics deployed in parallel, coinciding processes to intervene at the federal, state, institutional, and grassroots levels through legal court cases, lobbying (federal, state, city and county, and institutional), community planning, rallies, vigils, newspaper coverage, and media making. Some archival records were created and kept by community members who opposed the freeway, and other archival sources documented the actions and perspectives of the opposition. The archival materials describe how opposition movements against the freeway engaged in community-based organizing to lobby at legal, state, and federal levels, as well as engage in public education and protests to protect targeted sites in Moanalua, Kāneʻohe, and Hālawa valleys. While the first valley was saved from construction, the latter two were impacted. The freeway was constructed in portions, starting at different ends, then joining the parts in the middle.[1]

Moanalua

Indigenous community leaders who have ancestral, cultural, and pre-colonial knowledge of impacted places became important sources of information to influence legal and institutional lobbying to protect sites, as well as to rally communities.

Upon hearing of the intent of the H-3 freeway to build through Moanalua, Kanaka Maoli chantress Namakahelu Kapahikauaokamehameha provided information about the historical and cultural significance of sites throughout Moanalua Valley documented in oli (chants) passed down to her since many generations from the pre-contact Hawaiian society. This knowledge galvanized the Moanalua Gardens Foundation[2] to advocate for sites in Moanalua Valley to the National Historic Register in 1973.

In 1971, a coalition of different parties formed the Stop H-3 Association to oppose the Hawaiʻi State and Federal Departments of Transportation in their plans to construct the freeway through Moanalua Valley. Stop H-3 Association was composed of local and newcomer lawyers and community members committed to representing the communities who opposed the freeway.[3] They sued the State stating it was a violation of National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA), but District Court Judge Sam King decided that the freeway could move forward because the Hawaiʻi Historical Places Review Board found that Moanalua Valley did not have sufficient local significance. Boyce Brown, lead attorney for the Stop H-3 Association, pushed for another suit that the State needed an adequate Environmental Impact Statement in order to prove it was follow the Department of Transportation Act 4(f).

To appeal, the Moanalua Gardens Foundation traveled to Washington to meet with the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Rogers Morton, and shared the historical significance of Moanalua as orally documented by chantress Namakahelu and then written by Harriet Damon Baldwin of the Moanalua Gardens Foundation. The statement shared the genealogical roots of chantress Namakahelu, who was a practitioner of the chants and oral traditions that documented the pre-contact history of Moanalua Valley.[4]This information was included in the application to classify Moanalua Valley under the National Register of Historic Places. It persuaded the Secretary of the Interior to agree that Moanalua Valley–as a whole–was sacred and eligible for preservation. In 1976, the U.S. Court of Appeals reversed Judge King’s ruling and the U.S. Department of the Interior deemed the valley worthy of the National Register of Historic Places.[5]

The Reroute of the H-3 Freeway

When the H-3’s route through Moanalua Valley was defeated, the Hawaiʻi State Department of Transportation looked to a North Hālawa Valley route as the next option.[6]

In 1973, the H-3 Socio-Economic Study[7] was compiled and released by research consultants who outlined and analyzed different points of view about the H-3 project. The project compiled interviews of people in the Heʻeia-Kahaluʻu-Kualoa area, Hui Malama ʻĀina O Koʻolau, Hui Koʻolau, Kahaluʻu Coalition, Hawaii Rural Housing Development Corporation, Hawaii Department of Transportation, Honolulu Planning Department, the U.S. Soil Conservation Services, the University of Hawaiʻi’s Environmental Simulation Laboratory, Windward land developers, and concerned individuals. This report documented the talking points of community members for and against the freeway. The Stop H-3 Association recognized a split on public opinion about the freeway. Parts of the mainstream view, including parts of the Windward community in Kāneʻohe, were for the freeway. There were communities of opposition, such as in the Windward community of Kahaluʻu valley, where communities were concerned about the impact of more cars impacting the rural environment and lifestyle.[8]

Hui Malama ʻĀina o Koʻolau was an organization that was concerned about the H-3 freeway increasing the urbanization of the rural Kahaluʻu area. Their strategy was to increase educational curriculum about the Kānaka Maoli historical and cultural significance of the area.[9] Community groups created flyers[10] and statements to rally communities,[11] at the city and county, at the Legislature,[12] and at the University of Hawaiʻi,[13] around their point of view.

There were also pro-freeway perspectives.[14] Rick Ziegler, a later President of the Stop H-3 Association, wrote that the opposition perspective’s media and outreach campaigns were diluted and dwarfed by the pro-freeway perspective, which was led and funded by the Governor Administrations of John Burn and George Ariyoshi, the Congressional office of Senator Daniel Inouye, along with their full-time staff and resources who helped to outreach to the unions and other public organizations to support their side. Meanwhile, Stop H-3 Association worked on a grassroots level with volunteers lobbying neighborhood boards, university campuses, and Washington D.C. offices when possible. Zeigler also commented on the importance of the optics of the Stop H-3 Association so that it wouldn’t be seen as dominated by “loud-mouth haole environmentalists,” which could have further made them unpopular in the eyes of the local culture.[15]

In 1977, Bishop Museum was hired to identify sites of cultural importance in Hālawa Valley.[16] Construction was planned to begin from Kāneʻohe Marine Corps Base toward the Koʻolau mountains at Haʻikū Valley, and to exit on the south face of the Koʻolau mountains at Hālawa Valley. Concerned community groups began to activate once again.

In 1977, community members with lobbying experience at the State Legislature, Law Professor Jon Van Dyke[17] and Hawaiʻi Senator Norman Mizuguchi,[18] testified to pass House Resolutions to request the transfer of federal funds away from the H-3 freeway because of its social and environmental impacts, and instead, to use those funds to improve the H-1 and H-2 freeways that were more heavily used. Another way that the H-3 funds could be used was to develop a mass transit system.[19] E. Alvey Wright, former Hawaii State Transportation Director, wrote a Honolulu Advertiser opinion piece questioning the freeway route through Hālawa; he argued that funding H-3 could take away money from supporting H-1 construction updates that would address the movement of people from the west side of Oʻahu to Honolulu, where many commute to work.[20]

In 1978, Stop H-3 Association filed an amended complaint:

- The state changed the route of the freeway to Hālawa without holding public hearings

- Once the hearings were held, the location hearings and design hearings were held at the same time instead of the design hearings being held following the location hearings

- North Hālawa Valley was not a “ feasible and prudent” alternative because the cost was far greater than Moanalua Valley

- The freeway would disrupt important recreational areas[21]

In 1981, newspaper articles entitled “H-3 seen fatal to growth control” and “Foes of H-3 again muster their forces” document the work of the freeway opposition who continued to build public discourse on what sustainable planning could look like for the island. This goal would not be achieved through the H-3 freeway.[22]

In 1982, Stop H-3 Association filed a complaint listing 48 separate claims in opposition to the new Hālawa route.[23]

There was also lobbying happening at the federal level to shift funding away from the freeway’s development. On December 2, 1983, the Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration (FHA) responded to Hawaiʻi Representative Robert S. Nakata regarding the withdrawal of segments from the H-3 inter-state system and the transfer of funds to substitute other freeway projects. The FHA stated they would evaluate H-3 withdrawal requests because they do not consider H-3 to be unified and connected to the continental U.S. national inter-state system. But the FHA deferred the final decision to the Hawaiʻi state government because it was a local matter. The completion date of the freeway would be 1991-1992.[24] But on March 5, 1984, Senator Daniel Inouye sent a letter to Rep. Robert Nakata regarding the proposed construction of the H-3 Freeway, and that concerns would be sent to FHA. But this correspondence didn’t make sense because decisions also happen at Inouye’s Congressional level for inter-state funds.[25]

In 1984, the freeway construction began to encroach on the Hoʻomaluhia Botanical Garden. Stop H-3 Association argued that the freeway cannot build through Hoʻomaluhia Garden because it was parkland protected by the NEPA. To stay within the bounds of Section 4(f) of the Transportation Act, the No Build Alternative and the Makai Realignment should be considered. The State Department of Transportation appealed the imposition of the injunction, but the court denied it.[26]

Despite this, in 1986, Congress passed Public Law No. 99-551, 100 Stat. 3341, which included Section 114 exempting the H-3 from the requirements of Section 4(f) of the Transportation Act.[27]

In 1986, the Stop H-3 Association produced the 1986 booklet “The Truth About H-3: The Destructive billion-dollar highway that does nothing to solve Oahu’s contemporary transportation issues,” which outlined the inability of the freeway in meeting the public need, and directed supporters to increase their pressure on political leaders to redirect funds away from the H-3 and toward more useful transportation projects.[28] To engage communities that were in the planned route of the freeway, a flyer was published in the Honolulu Advertiser on March 27, 1986. It called for an H-3 Informational Meeting for the communities of Nuʻuanu, Kalihi, and Windward Oahu to learn more about the impacts of the Hawaiʻi State Department of Transportation plans for the Trans-Koolau freeway system that they have not been hearing about in the mass media, and how they could take action. The flyer provided dates, times, and school cafeteria meeting places for the information meeting.[29]

Kāneʻohe (Luluku Terraces and Kukuiokane Heiau) to Haʻikū Valley

Construction of the Kāneʻohe Interchange moved forward. In 1987, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) sued the H-3 freeway construction because of the discovery of the Luluku Terraces,[30]a site of pre-contact agricultural terraces dating to 500 A.D. that was, at the time, covered by banana patches.[31] In response to this suit, the State Department of Transportation said it would create an off-ramp to loop around the Luluku terraces. The Office of Hawaiian Affairs Board of Trustees [36] took a position to not be for or against the freeway, but to focus on the suit regarding the preservation of Luluku. The trustees want to ensure that “appropriated funds were not used to oppose building of the proposed H-3 freeway” because of agreements between OHA, the state, and federal governments to preserve Luluku.[37]

But in Marion Kelly’s presentation at the 1986 World Congress of Archaeologists, she mentioned that Luluku Terraces were not just confined to the area that the freeway ramp would loop around. In fact, it was a larger complex that included the Kukuiokāne Heiau, dedicated to the god Kāne, as well as burials in the area. She cited other archaeologists who agreed about the importance of their preservation. While she did receive audience support after her talk, and drafted a resolution in Support of the Preservation and Protection of the Luluku Agricultural Terraces, it was not brought up in the plenary session.[32]

The H-3’s construction from Kāneʻohe Marine Corps Base toward the Halekou Interchange was already completed by 1987. This gave the Hawaiʻi State Department of Transportation reason to press on with the construction since parts of it were already built.[33] By 1989, public controversy over the Kukuiokāne Heiau erupted.[34] Kanaka Maoli and local supporters disputed the Bishop Museum’s announcement that the Kukuiokāne Heiau didn’t exist. There was also concern that OHA was unable to take a stronger stance against the freeway when the larger Kukuiokāne Heiau complex, that Luluku was part of, was excavated.[35]

The opposition to the H-3 freeway also pointed to the dangers of the Omega radar station that was on the freeway route through Haʻikū Valley. Zeigler wrote,

“This is the Coast Guard OMEGA station, with its enormous antenna system spanning the valley ridge tops – 6 cables each over 1000 feet long running parallel to each other some 1200 feet above the valley floor. The overhead antenna wires are connected to the large green concrete station in the back of the valley with a massive download cable, and radiating outward from the station is a dense network of buried copper cables called the ground system, acting to absorb much of the radiated signal. H-3 then is planned to actually pass through the OMEGA antenna system, between the overhead spans and the ground system on a double row of concrete viaducts reaching 100 feet in height to meet the tunnel portals.”[38]

Zeigler raised that the OMEGA station’s radiation could impact the health[39] of workers and drivers going through that projected route.[40] While the 1988 U.S. Coast Guard Report and 1988-1989 newspaper articles cited the potential impacts of the Omega station, the Hawaiʻi State Department of Transportation insisted the impacts would be minimal.[41] A Japan firm was chosen to build the tunnel through the Koʻolau mountains so the freeway could exit on the other side to Hālawa Valley.[42]

Hālawa Valley

As construction at the Hālawa Interchange commenced, the Stop H-3 Association argued that Hālawa Valley should not be the site of the freeway because the Oʻahu ʻAlauahio (creeper) is a rare species of bird that is protected by the Endangered Species Act. But the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reaffirmed that the freeway would not interfere with endangered plants and animals.[43]

In 1990, as the freeway route entered Hālawa Valley, Bishop Museum found remnants of a luakini heiau complex. The freeway route was altered to preserve the luakini heiau complex.[44]

But in 1993, Barry Nakamura, Bishop Museum archaeologist, found that there were elements of a women’s heiau (known as Hale o Papa) connected to the luakini complex. The Bishop Museum rejected Nakamura’s findings as “a theory” and he was fired for violating museum policies.[45]

Nevertheless, grassroots community groups began to write press releases and letters, and engage communities in direct action at impacted locations. For example on March 5, 1992, community organization Na Koa Ikaika wrote a press release discussing the pork-barrelling of the Democratic Party for development projects like the freeway that disregarded Kanaka Maoli archaeological sites, such as the Kukuiokāne and Hale o Papa Heaiu, which were recognized by archaeologist Barry Nakamura. Na Koa Ikaika expressed disdain for the hypocrisy of the State of Hawaii by calling on “tourists [to] boycott the Unparadise State which shows contempt for Hawaiian religion and culture.”[46] On March 27, 1992, Lela M. Hubbard wrote to Department of Transportation Director Mr. Rex Johnson to change transportation policies because the Hālawa Heiau Complex was an important archaeological discovery. She discussed the policy changes that were needed to engage with impacted Kanaka Maoli and researchers of heiau sites.[47] Also, various news articles were published in April and May of 1992 of H-3 protestors holding vigils at various Hālawa sites believed to be heiau, to reclaim these sites as culturally significant, even when the Hawaiʻi State Transportation Department and Bishop Museum did not.[48]

In May of 1992, Kanaka Maoli scholars at the University of Hawaiʻi Mānoa challenged the Bishop Museum’s denial of the existence of heiau and cultural remains in impacted valleys.[49] Communities continued to organize testimonies, marches, vigils, and processions to demonstrate their opposition to the construction.[50] Public pressure on state agencies prompted some political leaders to raise questions about the costs of the freeway, which had already exceeded the initial price.[51] Newspapers reported the deaths of construction workers accidentally killed during the building of the freeway.[52] Activists claimed state agents were harassing them as they tried to vigil at sites.[53] The Bishop Museum was being criticized internally and externally.[54]

In the end, the freeway was completed and opened on December 12, 1997. Kanaka Maoli and supporter communities continued to protest its inauguration,[55] such as a marathon that allowed thousands of people to run across the freeway that damaged Indigenous cultural sites beneath it.[56] Moreover, the public did not receive the Bishop Museum reports about any documented artifacts or remains found during the freeway’s construction through Hālawa and other valleys.[57]

Present-Day Community Advocacy

The perspectives that were for the development of the H-3 freeway co-existed with and triggered voices in opposition. The freeway was ultimately constructed because U.S. Federal and Hawaiʻi State governments wanted to use federal funds to connect military bases. It is important to note the power differential that characterized the relationship and historical outcome between the discourses against the freeway and those for it. Among the vocal opponents to the freeway were community voices concerned about the freeway’s environmental and cultural impacts, but their efforts were outnumbered. U.S Congressional power was able to effectively strike down oppositional movement demands in the court and congressional system, and mainstream cultural and media institutions worked to cover up findings of archaeological sites affected by the construction. Haunani K. Trask, author of From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawai‘i, and a voice of opposition against the freeway, wrote:

“Modern Hawai‘i, like its colonial parent the United States, is a settler society; that is, Hawai‘i is a society in which the indigenous culture and people have been murdered, suppressed, or marginalized for the benefit of settlers who now dominate our islands…” [58]

The opposition against the H-3 freeway was just one among many oppositional movements that tried to question how decisions about land use are carried out in Hawaiʻi, and for whose interests does land development serve. Candace Fujikane critically describes how settler colonialism influences ethnic historical narratives that have been socialized to comply with U.S. development agendas:

“‘We working people of Hawai‘i cultivate the land and harvest the sea. We build every home, harbor, airport, and industry. Through the centuries we’ve fought loss of lands, evictions, low pay, unemployment, and unsafe working conditions… In this and other accounts, the different ethnic groups lay a claim to Hawai‘i by claiming the labor that went into building the plantation system, the industries, the roadways, the shopping centers, the schools, and new subdivisions—in short, the physical manifestations of U.S. settler colonialism in Hawai‘i.”[59]

Settler colonialism provides a lens to explain the power differential in which the freeway was constructed by U.S. Federal and Hawaiʻi State interests in collaboration with members of Hawaiʻi’s local population. But the significance of the documentation of opposition against the H-3 freeway challenges readers to recognize the presence of a Hawaiian people’s movement that challenged top down decision making for land use, and raised important views on how ethical land use decision making could look like. Specifically, this history of opposition against the H-3 reveals a critical debate on the purpose and function of infrastructure development in Hawaiʻi, and the existence of pre-contact Indigenous cultural sites across Oʻahu, so that the public can be informed to decide what culturally ethical, locally beneficial development needs to take into consideration in the present and the future.

Ironically, the construction of the freeway exhumed Kānaka Maoli historical and cultural sites that galvanized Indigenous communities to learn and reclaim these places as part of their own decolonial collective identity and Indigenous memory formation. The Kānaka Maoli peoples have not relinquished their national sovereignty, as stated in the 1897 Petition Against the Annexation of Hawaiʻi and the 1993 Apology Resolution Public Law 103-105 signed by President Bill Clinton. There is debate on the legitimacy of the 1959 plebiscite for Statehood according to international law. These legal histories were part of constructing a critical historical narrative of Kānaka Maoli that informed cultural advocates’ protests before, during, and after the H-3 freeway’s development, which coalesced with sympathetic environmental and allied organizations who had their own arguments to protest the freeway. It is the emergence of historical narratives of Hawaiian Sovereignty that continues to challenge and decenter the narrative of U.S. influence over Hawaiian lands. This historical narrative needs serious study and discussion by all peoples, Indigenous, settlers, local and newcomers, as the mainstream political operations of Hawai’i continue to operate according to U.S. Administrative rules. Therefore, the histories of opposition against the freeway become important archival resources to learn historical discourses of Hawaiian Sovereignty that are in tension with mainstream Hawaiʻi political understandings.

It is important to know that deeper access to these histories of Indigenous struggles entails building relationships with present-day community organizations advocating for ongoing Kānaka Maoli rights, decolonization, environmental rights, as well as critical, community-based research in legal advocacy and anthropology. Before and while these relations are made, people can do their homework by reviewing library and archival repositories that hold information on these historical narratives, organizations, and individuals, such as the documentations of those who opposed the H-3 freeway.

Communities who protested the H-3 freeway created documentary materials to preserve their perspective as to why they opposed its construction. Some examples of published resources that can be consulted are:

- Video Documentary Malama Hālawa: the caretaking of a valley by Na Maka O Ka ʻĀina covers the history of Hawaiian peoples who have ancestral and cultural ties to the Hālawa Valley, the second location where the H-3 freeway would be constructed through; the video shows their knowledge about this impacted location and reason for the opposition to the H-3 freeway. Discusses the controversial nature of the Trans-Koʻolau Trek, a ten-mile fun run across the newly constructed freeway as a way to inaugurate it to the public.

- Protest Documentation through Photographic Narration: Ē Luku Wale Ē by Piliāmoʻo (Mark Hamasaki and Kapulani Landgraf) and Dennis Kawaharada

- Nā Wahi Pana o Koʻolaupoko by Kapulani Landgraf for more place-based moʻolelo (traditional stories of places) of the lands affected by the construction of the H-3 freeway

- Website and video “Restoring the Historic Agricultural Lands of Luluku” documents the efforts of Mark Paikuli-Stride leading the restoration of agricultural terraces and kalo farming practices in Luluku. Luluku was one of the sites in Kāneʻohe that was damaged by the construction of the H-3 freeway.

Community groups were formed dedicated to stewarding the remains of the cultural sites impacted by the freeway. These are present day organizations that welcome students and researchers to connect and work with community leaders dedicated to Indigenous revitalization of the cultural sites impacted by the H-3 freeway.

- Koʻolau Foundation and the Koʻolaupoko Hawaiian Civic Club continue to do place-based, cultural education work days in Haʻikū Valley. Since the Omega station was decommissioned after World War II, this organization has been stewarding the land, and inviting educators, students, and community members to participate in clearing the overgrown vegetation. They also preserve stories about sacred sites throughout the valley, such as the heiau dedicated to Kanehekili, the God of Thunder. The Koʻolaupoko Hawaiian Civic Club continues to advocate at local and federal levels to rehabilitate and renovate the former Omega Radar Station building into a cultural center dedicated to preserving the valley’s spiritual and healing histories.[60] Mahealani Cypher, board member of the Koʻolau Foundation (formerly Stop H-3), and current day advocate for the rehabilitation of Haʻikū valley, has donated her personal papers to the Richard Kekuni Blaisdell Hawaiian National Archive.

- Nā Kūpuna a me Nā Kākoʻo o Hālawa (Malama Hālawa) in Hālawa Valley is an organization that conducts cultural education work days in the area where the Hale o Papa (women’s heiau) once was. There are work days to cut back vegetation as well as learn about the historical, cultural, and spiritual significance of the area and the valley. The connection between the women and men’s heiau complexes were damaged by the freeway. Today, communities are working with the State and Federal levels for the cultural and environmental revitalization of North Hālawa Valley because of its spiritual, cultural, and historical significance.[61]

- The College of Social Science Center for Service Learning (CSSSL) at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa houses the Mālama I Nā Ahupuaʻa (MINA) program that connects students, faculty, and researchers to engage in service learning at sites affected by the H-3 freeway’s construction. Hale o Papa in Hālawa and Haʻikū Valley near the decommissioned Omega Station are among the few sites that MINA connects stewarding organizations with students, researchers, and volunteers to learn more about the significance of these places, to take care of them, and to support the Indigenous revitalization of these places.

- Hawaiʻi Peace and Justice conducts action research on the demilitarization of Hawaiʻi. Its predecessor, American Friends Service Commitee-Hawaiʻi, was involved in supporting grassroots campaigns opposing the freeway because of the militarized purpose of its construction, and the impact on Kānaka Maoli cultural sites. Within the HPJ / AFSC-Hawaiʻi archive are news clippings and legislative testimonies that monitored the oppositional movements against the freeway.

Archival Repositories Consulted

Center for Oral History – Social Movements in Hawaii – Ethnic Studies Resources Collection – Opposition to H-3 https://scholarspace.manoa.Hawaii.edu/communities/ce9a264e-7837-4357-9895-c15b794ac858

Hawaii Peace and Justice (formerly AFSC-Hawaii) archival collections

The University of Hawaii School of Law Library Archives, H-3 Litigation Archive. http://archives.law.Hawaii.edu/exhibits/show/h-3-litigation-finding-aid

Marion Kelly Papers, the University of Hawaii Hamilton Library Archives

References

-

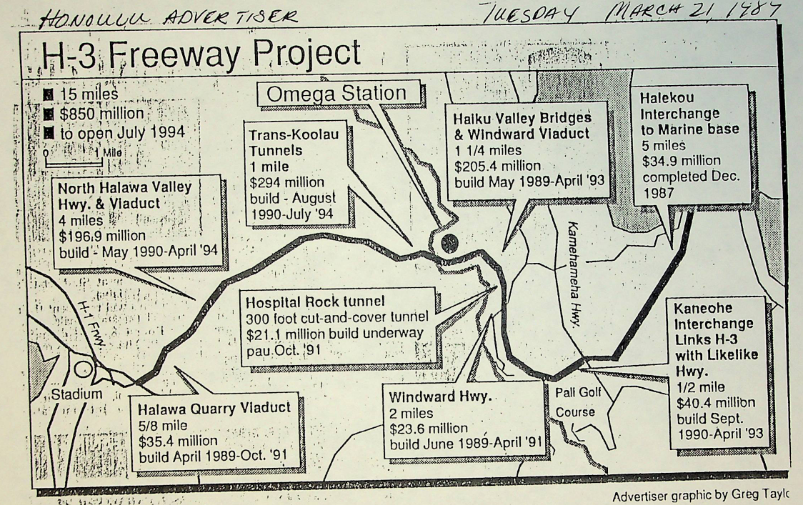

Honolulu Advertiser, “H-3 Freeway Project,” 21 March 1989. http://archives.law.Hawaii.edu/files/original/c39d313fe7265cfe3dcd44701cc28eea.pdf [accessed 24 July 2023]. (Collection: University of Hawai’i School of Law Library, H-3 Litigation Archive). ↑

-

Castro, Alex. “A letter from the president of Bishop Realty addressing the concerns of the State’s proposal to build a freeway through Moanalua Valley.” (1972). DOC510.pdf. [accessed 24 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History, Social Movements in Hawaiʻi, Opposition to H-3, Documents.) ↑

-

Boyce Brown, Robert Nakata, Denise DeCosta, Dee Dee Letts, and Rick Zeigler are among the active figures in the formation of the Stop H-3 Association. Leaders of the Stop H-3 Association would shift. Robert Nakata stepped down from the Presidency of the Stop H-3 Association in order to run for Hawai’i State Representative campaign. Cynthia Thielen joined as co-counsel to Boyce Brown. Ziegler, Rick. “Hawaii’s Road to Ruin – A Personal Account by Rick Ziegler,” (Self-Publication, 1990.) [accessed July 5, 2023.] (Collection: University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library, H-3 Litigation Archive) ↑

-

Baldwin, Harriet Damon, Frances MacKinnon Damon Holt, and John Dominis Holt. Statement on the Historical Significance of Moanalua. (U.S. Department of Interior, National Park Services, March 24,1973.) http://archives.law.Hawaii.edu/items/show/15607#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0 [accessed 26 April, 2023.] (Collection: Samuel P. King Collection) ↑

-

Glauberman, Stu. “Long, winding road of controversy over H-3.” Honolulu Advertiser, April 13, 1992. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/104965 [accessed 24 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Glauberman, Stu. “Long, winding road of controversy over H-3.” Honolulu Advertiser, April 13, 1992. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/104965 [accessed 24 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Eckbo, Dean, Austin & Williams with Morris G. Fox. “H-3 Socio-Economic Study: The Effects of Change on a Windward Oahu Rural Community.” 1973. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/79130 [accessed 27 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Ziegler, Rick. “Hawaii’s Road to Ruin – A Personal Account by Rick Ziegler,” (Self-Publication, 1990.) [accessed July 5, 2023.] (Collection: University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library, H-3 Litigation Archive) ↑

-

Naluai, Lucy Luka and Solomon D. K. Naluai. “Hawaiian Heritage Preservation Project Proposal. Grant Application Submitted by: Hui Malama Aina o Koʻolau Community Organization, Kahaluʻu, Oahu, Hawaiʻi.” 1974. https://evols.library.manoa.Hawaii.edu/items/7d18fe3f-cefd-421a-a5f5-9dd7683b5895 [accessed 27 July 2023]. (Collection: Daniel K. Inouye Collection). Eckbo, Dean, Austin & Williams with Morris G. Fox. “H-3 Socio-Economic Study: The Effects of Change on a Windward Oahu Rural Community.” 1973. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/79130 [accessed 27 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

“H-3 Means…” Dec. 14, 1973. https://scholarspace.manoa.Hawaii.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/096537ee-df2f-4345-a04a-a57cb288448a/content [accessed 27 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History).

“TH-3 Means Uncontrolled Development for the Island of Oʻahu,” n.d. https://scholarspace.manoa.Hawaii.edu/items/d1f50209-c2ac-44e8-bb4b-1590df597bfa [accessed 27 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

“H-3 Can Still Be Defeated,” 1974. https://scholarspace.manoa.Hawaii.edu/items/c5846238-0d7f-4873-9cb5-7aacd274ba40 [accessed 27 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

“Petition to the Governor and Legislators State of Hawaii,” n.d. https://scholarspace.manoa.Hawaii.edu/items/c8986b41-77e8-48dd-8a7d-c444eeeb5251 [accessed 27 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

“TH-3 Student Organizing,” 4 April 1975. https://scholarspace.manoa.Hawaii.edu/items/355f2004-35d0-4137-a0ea-201ad0a7f4c2 [accessed 27 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

“Get Behind H-3!” (Citizens for H-3, n.d.) https://scholarspace.manoa.Hawaii.edu/items/1d8ec25d-a8fc-42f2-b67c-44d1f455408c [accessed 27 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Ziegler, Rick. “Hawaii’s Road to Ruin – A Personal Account by Rick Ziegler,” (Self-Publication, 1990) [accessed July 5, 2023.] (Collection: University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library, H-3 Litigation Archive) ↑

-

Glauberman, Stu. “Long, winding road of controversy over H-3.” Honolulu Advertiser, April 13, 1992. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/104965 [accessed 24 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

“1977 Letter from Professor Jon Van Dyke to Governor George Ariyoshi in regards to the decision of the Department of Transportation to forge ahead with construction of the H-3 Freeway,” (1977) [accessed Aug 8, 2023.] (Collection: University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library, Jon Van Dyke Archival Collection); “Testimony before the Senate Transportation Committee relating to Rapid Transportation and the H-3 Freeway from Jon Van Dyke,” (1979) [accessed Aug 8, 2023.] (Collection: University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library, Jon Van Dyke Archival Collection); Testimony before the Board of Land and Natural Resources relating to the H-3 Freeway from Jon Van Dyke, including draft (1981.) [accessed Aug 8, 2023.] (Collection: University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library, Jon Van Dyke Archival Collection). ↑

-

“Statement of Senator Norman Mizuguchi on the status of Appropriations for Mass Transit and Testimony before the Senate Transportation Committee, relating to Rapid Transportation and the H-3 Freeway” (1979) [accessed Aug 8, 2023.] (Collection: University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library, Jon Van Dyke Archival Collection). ↑

-

Requesting the Transfer of Interstate H-3 Freeway Funds, H.R. No. 345, 12th Legislature 1983, House of Representatives, State of Hawaiʻi. ↑

-

Wright, E. Alvey “Transit, psychiatry, etc: ‘Submit H-3 Alternatives’” (Honolulu Advertiser, 1977) [accessed 8 Aug 2023]. (Collection: University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library, H-3 Litigation Archive). ↑

-

Sinclair, Gwen and Cachola, Ellen-Rae, “Judicial Process” Archives & Political Processes: Case Study of the H-3 Freeway, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2023, https://manoa.hawaii.edu/h-3/processes/judicial/ ↑

-

“Scrapbook Newspaper Articles, about OHA; about the reapportionment plan for the City Council; about trans-Koolau H-3 freeway. Book Reviews, River Basin, Planning, Theory and Practice; Groundwater in Hawaii – A Century of Progress; Coastal Upwelling,” (1981), Jon Van Dyke Archival Collection, BB1I2:66, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honoululu, HI. ↑

-

Sinclair, Gwen and Cachola, Ellen-Rae, “Judicial Process” Archives & Political Processes: Case Study of the H-3 Freeway, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2023, https://manoa.hawaii.edu/h-3/processes/judicial/ ↑

-

Barnhart, R. A. Withdrawal of segments from the Interstate System, Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration (1983) [accessed 8 Aug 2023]. Social Movements Collection, Center for Oral History, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI. ↑

-

Inouye, Daniel. Letter about the Construction of the H-3 Freeway, Social Movements Collection, Center for Oral History, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI. ↑

-

Stipulation to Modify Injunction to Restore Kamehameha Highway to Full Use (U.S. District Court 1984), H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library, Honolulu, HI; Order Denying Motion for Modification of Injunction (U.S. District Court of Hawaiʻi, 1984), H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Law Library, Honolulu, HI. ↑

-

Sinclair, Gwen and Cachola, Ellen-Rae, “Judicial Process” Archives & Political Processes: Case Study of the H-3 Freeway, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2023, https://manoa.hawaii.edu/h-3/processes/judicial/ ↑

-

Stop H-3 Association of Hawaiʻi. Booklet “The Truth About H-3: The Destructive billion-dollar Highway that does nothing to solve Oahu’s contemporary transportation problems” (January 1986), Jon Van Dyke Archive, 3A1(2):18, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Library, Honolulu, HI. ↑

-

H-3 Informational Meeting, the Honolulu Advertiser, 1986. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/79018 ↑

-

Sinclair, Gwen and Cachola, Ellen-Rae, “Judicial Process” Archives & Political Processes: Case Study of the H-3 Freeway, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, 2023, https://manoa.hawaii.edu/h-3/processes/judicial/ ↑

-

Kelly, Marion. “Preservation of the Luluku Agricultural Terraces, Hawaii and A Resolution in Support of the Preservation and Protection of the Luluku Agricultural Terraces in Kāneʻohe,” (World Archaeological Congress 1986), Marion Kelly Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI. ↑

-

Kelly, Marion. “Preservation of the Luluku Agricultural Terraces, Hawaii and A Resolution in Support of the Preservation and Protection of the Luluku Agricultural Terraces in Kāneʻohe,” (World Archaeological Congress 1986), Marion Kelly Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI. ↑

-

Stone, Bill. “Plan selected for Kāneʻohe Interchange on H-3.” Windward Sun Press, October 1987. (Collection: H-3 Litigation Archive). ↑

-

Glauberman, Stu. “Long, winding road of controversy over H-3.” Honolulu Advertiser, April 13, 1992. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/104965 [accessed 24 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Glauberman, Stu. “Long, winding road of controversy over H-3.” Honolulu Advertiser, April 13, 1992. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/104965 [accessed 24 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Keale, Moses K. Sr. Opinion “H-3 and OHA.” Honolulu Advertiser, 1987. (Collection: H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Law Library). ↑

-

Glauberman, Stu. “Long, winding road of controversy over H-3.” Honolulu Advertiser, April 13, 1992. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/104965 [accessed 24 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Ziegler, Rick. “Hawaii’s Road to Ruin – A Personal Account by Rick Ziegler,” (Self-Publication, 1990) [accessed July 5, 2023.] (Collection: University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library, H-3 Litigation Archive) ↑

-

“Letter enclosed with document United States Coast Guard Action.” (U.S. Coast Guard, 1988) [accessed April 26, 2023] H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Law Library . ↑

-

Glauberman, Stu. “Long, winding road of controversy over H-3.” Honolulu Advertiser, April 13, 1992. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/104965 [accessed 24 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Borg, Jim. “Omega hazards still H-3 construction worry.” Star-Advertiser, 1989. (Collection: H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library); Borg, Jim. “Coast Guard report warns of Omega radiation threat to H-3.” Honolulu Advertiser, 1988. (Collection: H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library); Borg, Jim. “Further warning of Omega/H-3 danger.” Honolulu Advertiser, November 19, 1988. (Collection: H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library); Asato, Bart. “State declares H-3 risks ʻare minimal.’” (Star-Bulletin & Advertiser, 1988). (Collection: H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library); Yamaguchi, Andy. “H-3 shield designed to protect drivers from Omega signals” and “H-3 Freeway Project.” Honolulu Advertiser, March 21, 1989. (Collection: H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library); “H-3 Construction Plans” and Young, Lucy “H-3 Shakes off last of legal barriers” Star-Bulletin, 1989. (Collection: H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library). ↑

-

“Japan firms cleared to bid on H-3 project.” Star-Bulletin, 1989. (Collection: H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi School of Law Library). ↑

-

“State of Hawaii Department of Transportation cover letter to Mr. Boyce R. Brown, Jr. from Edward Y. Hirata.” (1987), H-3 Litigation Archive, H3B1:57, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Law Library, Honolulu, HI; Stop H-3 Association of Hawaiʻi. Booklet “The Truth About H-3: The Destructive billion-dollar Highway that does nothing to solve Oahu’s contemporary transportation problems” (January 1986), Jon Van Dyke Archive, 3A1(2):18, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Library, Honolulu, HI.; “Opinion (9TH CIR): Stop H-3 Association et al v. Elizabeth Dole et al” (Ninth Circuit Court, November 29, 1983) [accessed 21 June 2023], H-3 Litigation Archive, 18.2, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Law Library. ↑

-

Glauberman, Stu. “Long, winding road of controversy over H-3.” Honolulu Advertiser, April 13, 1992. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/104965 [accessed 24 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Glauberman, Stu. “Long, winding road of controversy over H-3.” Honolulu Advertiser, April 13, 1992. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/104965 [accessed 24 July 2023]. (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Hubbard, Lela M. “Press Release from Na Koa Ikaika.” (March 25, 1992), ScholarSpace, Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3 Collection, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI. ↑

-

Hubbard, Lela M. “Press Release from Na Koa Ikaika.” (March 25, 1992), ScholarSpace, Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3 Collection, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI. ↑

-

“H-3 protesters planning religious rites at Site 75,” (Honolulu Advertiser, April 8, 1992), ScholarSpace, Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI; “200 Hike into Valley, Visit Sites,” (Honolulu Advertiser, April 13, 1992), ScholarSpace, Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI; “No evidence yet on heiau, the state says,” (Honolulu Advertiser April 14, 1992), ScholarSpace Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI; “H-3 routing around heiaus would cost $5 million,” (Honolulu Advertiser, April 25, 1992), ScholarSpace Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI; “H-3 can bypass controversial sites, officials say,” (Honolulu Advertiser, May 1, 1992), ScholarSpace Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI ↑

-

“H-3 sites downgraded: Museum says the areas were not sacred,” (Honolulu Advertiser, May 1, 1992), Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI; 5/5/1992 “UH scholars rip site report,” (Honolulu Advertiser, May 5, 1992), ScholarSpace, Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI; “Hālawa Coalition Statement” (May 9, 1992). ScholarSpace, Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI. ↑

-

“H3-Hālawa Valley debate flares again at meeting,” (Honolulu Advertiser, May, 16 1992). ScholarSpace, Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI; Kelly, Marion. “Who Needs H-3?” (May 22, 1992), Marion Kelly Papers, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI; Glauberman, Stu, “Activists plan process, rites to save ancient sites,” Honolulu Advertiser, June 6, 1992. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/104979 [accessed 24 July 2023). (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History); “Malama Halawa Flyer: Stop H-3” (Pro-Hawaiian Sovereignty Working Group and Mālama Halawa, June 7, 1992). (Collection: ScholarSpace Center for Oral History); Hubbard, Lela. “Letter from Lela Hubbard to the Editor regarding the Democratic boondoggle,” ScholarSpace, Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3, Honolulu, HI; “Protest Groups Seek Reburials,” (Honolulu Advertiser, September 7, 1992). ScholarSpace, Center for Oral History, Opposition to H-3, Honolulu, HI. ↑

-

Yamaguchi, Andy; Glauberman, Stu. “State report says two H-3 sites not sacred,” Honolulu Advertiser, September 10, 1992. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History).

Kresnak, William. “Trask: State lawsuit threat doesn’t faze H-3 protestors,” Honolulu Advertiser, February 10, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Pang, Gordon Y.K. “Construction Cost 2 lives, several injuries,” Honolulu Advertiser, December 4, 1997. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History). ↑

-

Catterall, Lee. “Hālawa H-3 activists say state filmed their doings,” Honolulu Advertiser, March 15, 1993. (ScholarSpace, Center for Oral History), Tangonan, Shannon. “Hālawa Activists say state harassing them,” Honolulu Advertiser, March 15, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History) ↑

-

“Nakamura, Barry. “Violations of the H-3 Memorandum of Agreement and Federal Law.” March 24, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History) ↑

-

Watanabe, June. “Hālawa heiau vigil preserved,” Honolulu Advertiser, April 2, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); Catterall, Lee. “100 make spiritual trek into Hālawa Valley,” Honolulu Advertiser, April, 5, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); “Hālawa Valley, a year later…,” Honolulu Advertiser, April 5, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); “Hālawa Valley still in dispute: Heiau activists say objections unresolved,” Honolulu Advertiser, April 6, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); Morse, Harold. “H-3 opponents hit highway,” Honolulu Advertiser, August, 30, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); Tanahara, Kris M. “Marchers mark delay in Hālawa Valley work,” Honolulu Advertiser, August 30, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); “H-3 Freeway opponents call for audit of cost overruns,” Honolulu Advertiser, December 21, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); Dayton, Kevin. “H-3 changes, wealth boost price tag by $269 million,” Honolulu Advertiser, December 21, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); Omandam, Pat. “H-3 realignment will still disturb heiaus, group says,” Honolulu Advertiser, December 22, 1993. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); Kakesako, Gregg K. “Which comes first, autos or H-3 report,” Honolulu Advertiser, April 24, 1995. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); “H-3 archaeology: Public deserves clear answers,” Honolulu Advertiser, June 3, 1996. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); Waite, David. “Museum President Defends Archaeology on H-3,” Honolulu Advertiser, June 3, 1996. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); Waite, David. “Official tried to forestall comments,” Honolulu Advertiser, June 3, 1996. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); Waite, David. “Museum’s H-3 hiring questioned,” Honolulu Advertiser, June 10, 1996. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); Kame’eleihiwa, Lilikala. “H-3 Story: ‘A Great Injustice’,” Honolulu Advertiser, August 11, 1996. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); “H-3: The Long and Winding Road,” Honolulu Advertiser, December 3, 1997. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); Omandam, Pat. “Rocky Road: Even with the opening at hand, many Hawaiians say protests may not end,” Honolulu Advertiser, December 4, 1997. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History); ↑

-

“H-3: Protests May Continue, many Kanaka Maoli say.” Honolulu Advertiser, December 4, 1997 [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History) ↑

-

“Opening precedes land reports.” Honolulu Advertiser, December 4, 1997. [accessed July 27, 2023]. (Collection: Center for Oral History) ↑

-

Trask, Haunani. From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawai‘i. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press: 1993. ↑

-

Candace Fujikane. “Introduction: Asian Settler Colonialism in the U.S. Colony of Hawaii.” In Asian Settler Colonialism: From Local Governance to the Habits of Everyday Life in Hawaii, 2008, pp. 1-42. ↑

-

Cypher, Mahealani. “Haʻikū Valley Cultural Preserve.” (Koʻolau Foundation, 2023) H-3 Litigation Archive, University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Law Library, Honolulu, HI. ↑

-

Tanaka, Nicholas. “Hālawa Valley Mālama ʻĀina: The Stewards of Hālawa Valley.” Plan B Project for MA in Hawaiian Studies, University of Hawaii at Mānoa, 2009. ↑