Judicial Process

Introduction

When trying to research the court cases involving the H-3, it is important to get a sense of the judicial systems and processes where these cases took place. H-3 cases were heard at state and federal courts. Knowing this can help researchers understand the organization of court records. This essay will describe the structure of Hawai’i’s Judicial System, and the U.S. Federal Court System that includes the District Courts, Court of Appeals, and the Supreme Court. By understanding these judicial roles and processes, it can contextualize how and why H-3 cases were litigated across these different courts.

Hawaiʻi’s Judicial System

There are four levels of courts in Hawaiʻi’s Judicial System (the bottom three rectangles of this hierarchical tree structure):

- Trial Courts

- Circuit: Jury trials, civil & criminal, probate, criminal

- Oʻahu: First Circuit

- Maui: Second Circuit

- Hawaiʻi Island: Third Circuit

- Kauaʻi: Fifth Circuit

- Land: part of the First Circuit Court that addresses registration of title to land and easements or rights in land held and possessed

- Tax Appeal: part of the First Circuit court that addresses property, excise, liquor, tobacco, income and insurance

- Environmental: part of the Circuit and District courts that addresses water, forests, streams, beaches, air, mountain, terrestrial and marine animals

- Family: children, delinquent, waiver status, abuse and neglect, terminate parental rights, adoption, guardianship, domestic-relations, divorce, non-support, parentage, child custody

- District Courts: First to Fith Circuits are located on O’ahu, Maui, Hawai’i, and Kaua’i, respectively. They address traffic, landlord-tenant, debt amount, damage, and property

- Circuit: Jury trials, civil & criminal, probate, criminal

- Intermediate Court of Appeals (the middle rectangle): hears appeals from state trial courts or agency decisions. Under some circumstances, it is subject to Hawai’i Supreme Court

- Hawai’i Supreme Court (top rectangle): hears appeals from lower courts or intermediate court of appeals; court rules, licensing, and discipline of attorneys. The Law Library collects, organizes and disseminates information and materials related to legal research and judicial administration.[1] Boards and Commissions provide an opportunity for citizens to have a voice in their government and provide a means of influencing decisions that shape the quality of life for the residents of Hawaii.[2]

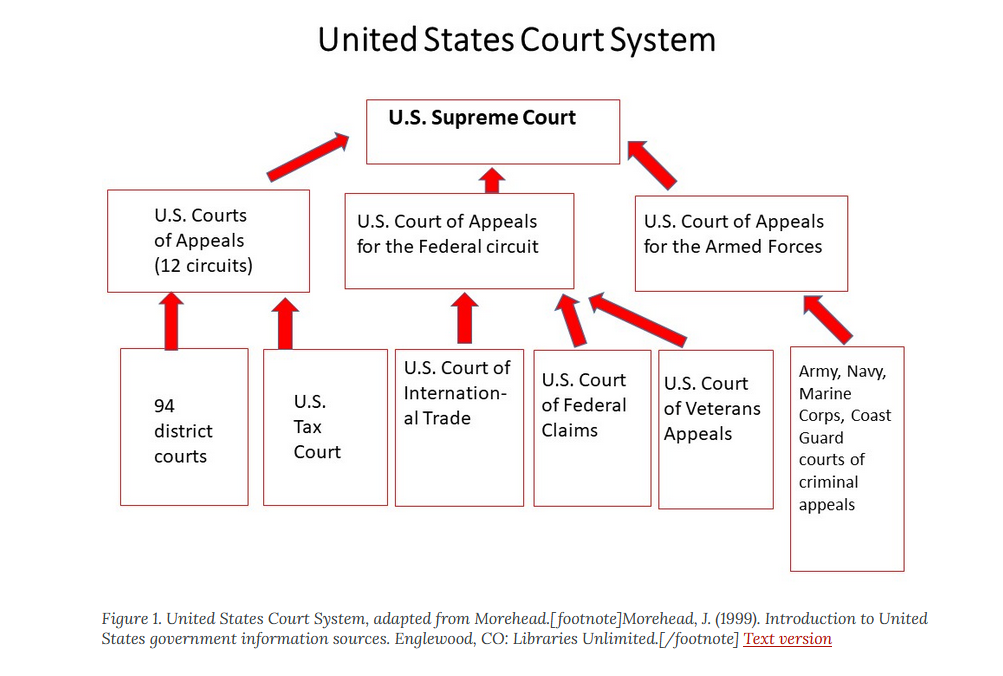

United States Federal Court System

Federal courts hear cases involving the constitutionality of a law, cases involving the laws and treaties of the U.S. ambassadors and public ministers, disputes between two or more states, admiralty or maritime law, and bankruptcy cases.[3]

From: Sinclair, Gwen. https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/lis648/chapter/judicial-branch-and-legal-information/

Under the Supreme Court, there are 94 federal district or trial courts, also known as U.S. District Courts. The District Courts are the civil and criminal trial courts of the federal court system. They determine if the facts and legal principles have been applied in the decision. There is one district court in each state and the District of Columbia, and within them are bankruptcy courts.[4] Hawai’i has a United States Federal District Court, which is a trial court of the U.S. federal courts; it handles civil and criminal cases as a court of law and equity; bankruptcy court; appeals go to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

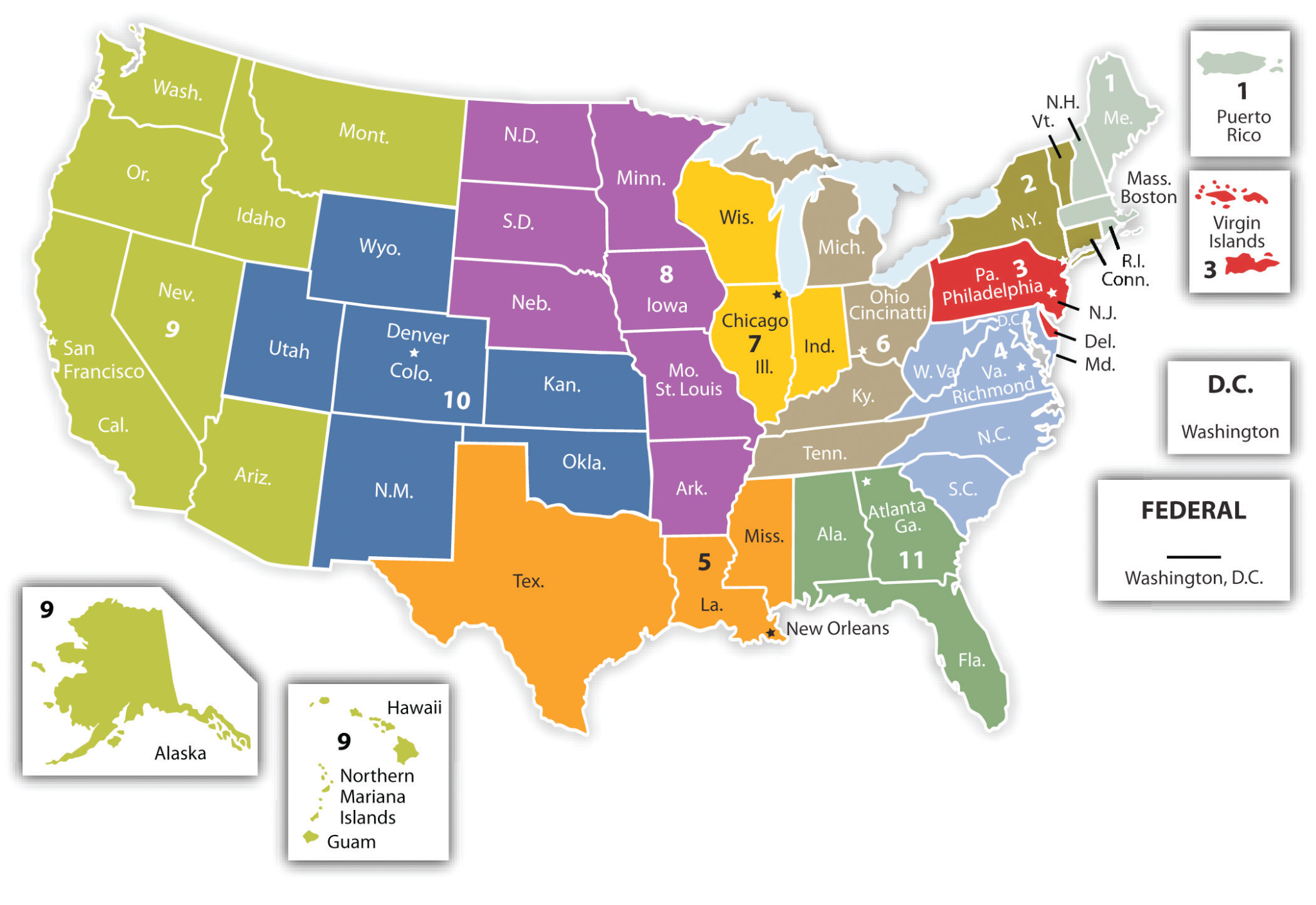

U.S. Court of Appeals (12 circuits)

The U.S. Court of Appeals has 12 circuits representing specific regions. Hawai’i is part of the Ninth Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals. There is also the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal circuit and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces. The Court of Appeal’s tasks are to determine whether or not the law was applied correctly in the trial court. They can hear challenges to district court decisions from courts located within its circuit as well as appeals from decisions of federal administrative agencies. They can also hear appeals in specialized cases involving patent laws.

Parties file “briefs” to the court, arguing why the trial court’s decision should be “affirmed” or “reversed.” After the briefs are filed, the court will schedule “oral argument” in which the lawyers come before the court to make their arguments and answer the judges’ questions. Though it is rare, the entire circuit court may consider certain appeals in a process called an “en banc hearing.” (The Ninth Circuit has a different process for en banc than the rest of the circuits.) En banc opinions tend to carry more weight and are usually decided only after a panel has first heard the case. Once a panel has ruled on an issue and “published” the opinion, no future panel can overrule the previous decision. The panel can, however, suggest that the circuit take up the case en banc to reconsider the first panel’s decision.[5]

Appeals from the U.S. Court of Appeals can be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court. The Supreme Court is the highest court in the US legal system that decides on all cases brought in federal court, or those cases from state court but dealing with federal law. After the circuit court or state supreme court has ruled on a case, either party may choose to appeal to the Supreme Court. But unlike the circuit court of appeals, the Supreme Court is not required to hear the appeal. Parties may file a “writ of certiorari” to the court asking the Supreme Court to hear the case. If the writ is granted, the Supreme Court will take briefs and conduct oral arguments. If the writ is not granted, the lower court’s opinion stands. The Supreme Court typically hears cases when there are conflicting decisions across the country on a particular issue or when there is a blatant error in a case.[6]

The US federal court system can hear cases authorized by the US Constitution or federal statutes; state cases can be reviewed by federal courts as a diversity jurisdiction under certain rules; state criminal prosecutions may be heard at federal level if the crime violated federal laws. The U.S. courts of appeals have the power to set legal precedence, influence U.S. law, and often the final arbiter on most federal cases because few cases are selected to be heard by the Supreme Court.

The Role of State and Federal Courts in the H-3 Cases

In the environmental review process and permitting process for public works projects, there are many opportunities for interested parties to contest the conclusions of decision makers. Opponents of a project can file suit in state circuit or federal district court to prevent state or federal agencies from taking actions that the plaintiffs believe are not in accordance with laws or regulations. If the cases go to trial, a judge renders a decision. The losing party can then file an appeal with an appellate court to request a review of the judge’s decision. The parties can also negotiate a settlement of the issues without going to trial. In addition to filing a lawsuit, a party can petition a judge to impose an injunction to stop certain actions while information is gathered or until certain conditions are met.

An individual judge can have an enormous impact on the outcome of a court case. During the course of the planning and construction of H-3, federal Judge Samuel Pailthorpe King issued a number of rulings and injunctions over a period of years. He was the sole federal judge in Hawaiʻi during much of his term, which covered 1972-1984, and he also issued rulings on several other important cases.

A lawsuit can be filed in state court if it involves state law or the actions of a state agency. Cases heard in federal court involve federal laws or the actions of federal agencies. In the case of H-3, lawsuits were filed in both state and federal court. Knowing whether a case was heard in state or federal court is essential for determining where to go to view the court’s decisions and the court records. In addition, the location of court records varies depending upon the dates of documents.

Case names list the names of the parties, i.e., the plaintiff(s), or complaining parties, and defendant(s). Plaintiffs in a lawsuit can be individuals or groups, such as Stop H-3 Association. Furthermore, multiple groups can join together to file a court action. Defendants can be individuals, companies, organizations, or government entities. In the H-3 litigation, lawsuits were filed naming the U.S. Secretary of Transportation as a defendant. Because various individuals served as Secretary of Transportation, the name of the case had to be changed when the officeholder changed.

Plaintiffs must demonstrate that they have “standing” to file suit; in other words, they must demonstrate that they have been or will be harmed by an action. They must also demonstrate that a ruling by the court is necessary to remedy the situation.

Federal Court Actions and Cases Involving H-3

July 1972

Stop H-3 Association, Life of the Land, Moanalua Valley Community Association, and Haiku Village Community Association filed suit against the Secretary of Transportation, Claude S. Brinegar [later Stop H-3 Association v. Volpe (No. 72-3606, D. Hawaii, Julv 6, July 13, 1973)]

(later consolidated with Civil No. 73-3794, filed on April 9, 1973). They were joined by individual plaintiffs and later Moanalua Gardens Foundation joined as an intervenor. The chief complaint was that the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) had failed to comply with Section 102(2)(C) of the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 by approving funding for construction of H-3 to begin before an EIS had been approved. In addition, the suit claimed that the state had not done exhaustive research on the environmental, economic, and social impacts of H-3, that the USDOT could not approve the project unless it conformed with local urban planning objectives, that H-3 had not been added to the Oʻahu General Plan and therefore no long-range studies on it had been completed, and that the road could not be routed through a park unless no alternative existed. The suit also claimed that the H-3 freeway violated state policy to encourage population decentralization.

September 1972

Hui Malama Aina o Koʻolau and several individuals filed suit against the City and County of Honolulu and City planning director Robert Way in state circuit court. The suit alleged that the City had not amended the Oahu General Plan to include the H-3 freeway.

October 1972

Judge Samuel P. King of the U.S. District Court issued an injunction to stop construction until the EIS was completed and approved. (Stop H-3 Association v. Volpe, 349 F.Supp. 1047 (D. Hawaii 1972))

April 1973

A new complaint, Civil No. 73-3794, was filed on April 9, 1973, by additional plaintiffs. Because the complaint included issues not raised in the case previously filed (Civil No. 72-3606), Judge King refused to allow Hui Malama Aina o Koʻolau to join the previous suit, telling them that they should file a separate suit. Later, the plaintiffs in Civil No. 73-3794 agreed to a dismissal of certain of their claims, which rendered the issues in both actions identical. At that point, the two suits were consolidated.

May 1973

Judge King held hearings to determine the answers to these questions:

- Is a new EIS required now that the design has been changed to have four vehicular lanes with two lanes for mass transit instead of six vehicular lanes?

- Were the location hearings held in 1965 and design hearings held in 1970 conducted properly in accordance with federal laws and guidelines?

- Did those hearings adequately address the social and environmental impacts of the freeway?

June 1973

Judge King ruled that the state had to submit a revised preface to the EIS to federal and state agencies for comment. The state had attached a revised preface to the EIS stating that the freeway would be reduced from six to four lanes and sent it to the President’s Council on Environmental Quality for approval without giving it to state and federal agencies to review it. (Life of the Land v. Brinegar, 485 F.2d 460, 472 (9th Cir. 1973), cert. denied, 416 U.S. 961 (1974). [not available online])

December 1974

Upon completion of the EIS in 1974 and its acceptance by the Federal Highway Administration, Judge King lifted the injunction and ruled that the project did not require a 4(f) statement.¹ Stop H-3 Association v. Brinegar, 389 F. Supp. 1102, 1117 (D. Haw. 1974)

January 1975

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that construction had to stop until it was determined that the freeway could go through Moanalua Valley.

1976

The plaintiffs appealed Judge King’s decision to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. The Ninth Circuit overturned Judge King’s 1974 ruling and reimposed the injunction. The appeals court ruled that Section 4(f) of the DOT Act applied, so a supplemental EIS was required to address Section 4(f). The USDOT subsequently filed a 4(f) statement but then the route of the freeway was changed. (Stop H-3 Ass’n v. Coleman, 533 F.2d 434 (9th Cir.), cert. denied, 429 U.S. 999, 97 S. Ct. 526, 50 L. Ed. 2d 610 (1976))

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that because Moanalua Valley was eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, the freeway could not be built there.

1977

The state DOT petitioned the court to drop the requirement for a supplemental EIS since the route was changed from Moanalua to Halawa. The court denied the motion, stating that a supplemental EIS was still required because the site had changed.

July 1978

Stop H-3 filed an amended complaint. It included the following amendments:

- The state changed the route of the freeway to Halawa without holding public hearings

- Once the hearings were held, the location hearings and design hearings were held at the same time instead of the design hearings being held following the location hearings

- North Halawa Valley was not a “ feasible and prudent” alternative because the cost was far greater than Moanalua Valley

- The freeway would disrupt important recreational areas

November 1978

Judge King ordered a 4(f) statement for Hoʻomaluhia Park. A supplemental EIS and a 4(f) statement for Hoʻomaluhia Park were later approved.

1982

Stop H-3 Association et al. filed a complaint listing 48 separate claims in opposition to the new Halawa route. After a 1981 trial, Judge King ruled that NEPA requirements had been met and construction could continue, and he lifted the injunction. He ordered that a second supplemental EIS be prepared to address new and significant information regarding the H-3/OMEGA Collocation Studies, the FHWA Region Nine Staff Analysis, and the Hoʻomaluhia Park 4(f) statement. The Secretary of Transportation’s determinations for the December 1974 Pali Golf Course 4(f) statement and the November 1980 Hoʻomaluhia Park 4(f) statement were set aside by the court. (Stop H-3 Association v. Lewis, 538 F. Supp. 149 (D. Hawaii 1982))

August 1984

Stop H-3 Association filed an appeal of Judge King’s lifting of the injunction and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reimposed the injunction (Stop H-3 Association v. Dole, 740 F.2d 1442 (9th Cir. 1984), cert. denied, 471 U.S. 1108, 105 S. Ct. 2344, 85 L. Ed. 2d 859 (1985).) The Ninth Circuit affirmed the District Court’s ruling, except that under Section 4(f) the record did not support the rejection of the No Build Alternative and the Makai Realignment. Thus, the court determined that the requirements of Section 4(f) had not been satisfied.

1985

The state Department of Transportation appealed the reimposition of the injunction by the District Court to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, claiming that the District Court had abused its discretion by reimposing the injunction. The court denied the appeal. (Stop H-3 Association et al v. Wayne J. Yamasaki, 85-1660 (9th Cir. 1985)).

1986

In 1986 the Continuing Appropriations Bill for Fiscal Year 1987, Pub. L. No. 99-500, 100 Stat. 1783 (later reenacted as Pub. L. No. 99-551, 100 Stat. 3341 because of clerical errors in the original enactment) included Section 114 which exempted H-3 from the requirements of Section 4(f) of the Transportation Act. Stop H-3 Association, Life of the Land, and Hui Malama Aina o Koʻolau, plaintiffs, challenged the constitutionality of section 114 in the case Stop H-3 Association v. Dole [Elizabeth Dole, U.S. Secretary of Transportation]. Federal judge Samuel King dismissed the lawsuit in May 1987, at which point the plaintiffs appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. (Stop H-3 Association v. Dole, 870 F.2d 1419 (9th Cir. 1989)) Oral arguments before a three-judge panel of the appeals court took place in November 1987. The court held that a federal law exempting H-3 from environmental protection laws did not violate equal protection of Hawaiʻi’s citizens.²

May 1987

The District Court terminated the injunctions that barred the design and construction of the H-3 project. The opponents appealed to the Ninth Circuit. Their motion for an emergency injunction was denied by the Ninth Circuit. (Stop H-3 Association, Life of the Land, Hui Malama Aina O Ko’olau, plaintiffs-appellants, v. Elizabeth Dole; William R. Lake As Hawaii Division Engineer, Federal Highways Administration; and Edward Hirata, As Director of the Department of Transportation Of The State of Hawaii, Defendants-appellees.*, 870 F.2d 1419 (9th Cir. 1989))

March 1989

A three-judge panel (Judges Schroeder, Pregerson, and Brunetti) from the Ninth Circuit heard an appeal of Judge King’s ruling. In its decision, the court remanded the case back to Judge King. The decision refuted many of the claims made by the plaintiffs. The State of Hawaiʻi filed an appeal with the U.S. Supreme Court, which declined to hear the case. (U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit – 870 F.2d 1419 (9th Cir. 1989))

State Court Actions and Cases Involving H-3

June1983

State Circuit Court Judge Wakatsuki ruled that the Board of Land and Natural Resources (BLNR) erred in issuing a Conservation District Use Application (CDUA) for construction of H-3 without holding a contested case hearing.

November 1983

BLNR held a contested case hearing and issued a Decision and Order granting the CDUA.

August 1984

Stop H-3 Association filed suit in Circuit Court (Stop H-3 Association v. State of Hawaii, Department of Land and Natural Resources, Civ. No. 69450 (1st Cir. July 12, 1983)) to contest the BLNR’s issuance of the CDUA. Stop H-3 Association, Life of the Land, Conservation Council for Hawaii, Sierra Club, Hawaii Chapter, and Hui Malama Aina o Koʻolau were plaintiffs.The circuit court entered an order affirming the Board’s decision on August 20, 1984. The plaintiffs appealed the decision to the state Supreme Court.

September 1985

The state Supreme Court affirmed the circuit court’s decision in Stop H-3 Association v. State Department of Transportation, 706 P.2d 446 (1985).

1987

The Office of Hawaiian Affairs (OHA) filed suit to prevent construction that would damage archaeological features in Luluku Archaeological District. OHA and the State Department of Transportation reached an agreement whereby a ramp would be relocated to avoid the archaeological sites.

Where to Find Court Records

Federal Trial Courts

Decisions of federal district courts are available in a number of repositories:

- HeinOnline (available in law libraries)

- Federal Supplement (available in law libraries)

- Google Scholar (subscription)

- Justia

- GovInfo

Records such as transcripts and pleadings in federal court cases filed from 2006 to the present are available electronically in PACER. Docket sheets for cases filed from 1993-present are also available electronically. Be aware that to use PACER, a researcher must sign up for a free account. There is a fee of $0.10 per page to view documents in PACER. If you accrue $30 or less of charges in a quarter, fees are waived for that period. Transcripts can be requested from the court reporter (on the case docket, refer to the minute entry designated as an Entering Proceeding (EP) for the court reporter’s contact information).

An alternative to PACER is the CourtListener RECAP Archive. The RECAP browser extension allows the archiving of PACER documents by PACER searchers who have installed the extension. The archived files are freely available and searchable in the CourtListener RECAP Archive. Note that the archive just contains PACER documents captured by users who searched PACER while they had the extension installed, so it contains only a subset of all PACER documents.

For court records in cases filed prior to 2006, a researcher must go in person to the district court in which the case was heard. The U.S. District Court of the District of Hawaiʻi is located in the Prince Kūhio Federal Building. A card catalog and microfiche provide information for cases from 1977-1993. Some case files have been transferred to the Federal Record Center and National Archives and can be retrieved by the District Court.

Federal Appellate Courts

PACER is also used for federal appellate court records. In addition, the Supreme Court Law Library in Honolulu maintains historical holdings of records and briefs from the appellate courts in Hawaiʻi.

U.S. Supreme Court decisions are available as follows:

- United States Reports (also in law libraries)

- Justia

State Trial Courts

Dockets of state trial court cases from 1984-present are available in the eCourt Kokua database. The full text of filings for recent cases (~past three years) can be downloaded for a fee. To obtain copies of filings in older cases (1970-present), a researcher must visit the relevant court in person. The Hawaiʻi State Archives provides access to Hawaiʻi Judiciary Branch records ranging from 1839-1970.

State Appellate Courts

The Hawaiʻi State Judiciary maintains electronic access to appellate court decisions and orders from 1998-present: https://www.courts.state.hi.us/opinions_and_orders. Decisions and orders are also available in eCourt Kokua. For older cases, consult the Hawaiʻi State Archives. Other sources for Hawaiʻi Supreme Court decisions include:

- Hawaii Reports (law libraries)

- Justia

- LLMC Digital (subscription)

Endnotes

¹Section 4(f) of the U.S. DOT Act of 1966 (49 U.S.C. § 303) “provides that the Secretary of Transportation may approve a transportation program or project requiring the use of publicly owned land off a public park, recreation area, or wildlife or waterfowl refuge of national, state, or local significance, or land of an historic site of national, State, or local significance, only if there is no feasible and prudent alternative to the using that land and the program or project includes all possible planning to minimize harm resulting from the use.”

² Hazel Glenn Beh and Velma S. Kaneshige, “Stop H-3 Association v. Dole: Congressional

Exemption from National Laws Does Not Violate Equal Protection,” University of Hawaii

Law Review 12, no. 2 (Fall 1990): 405-434.

-

“About.” Hawai’i State Law Library System, n.d. https://histatelawlibrary.com/about/ ↑

-

“Boards and Commissions.” State of Hawai’i, 2023 https://boards.hawaii.gov/ ↑

-

“Court Role and Structures.” United States Courts, n.d. https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/court-role-and-structure ↑

-

https://www.uscourts.gov/about-federal-courts/court-role-and-structure ↑

-

https://www.justice.gov/usao/justice-101/federal-courts#:~:text=The%20federal%20court%20system%20has,appeal%20in%20the%20federal%20system. ↑

-

https://www.justice.gov/usao/justice-101/federal-courts#:~:text=The%20federal%20court%20system%20has,appeal%20in%20the%20federal%20system. ↑