The location of the prime meridian and the time zones demonstrate that even the most straightforward mathematical and scientific systems of classification and measurement are not immune to political arguments and boundaries.┬Ā

┬Ā

The Prime Meridian

The designation of a line of longitude as the prime meridian (0┬║) is arbitrary, unlike the degrees of the parallels of latitude that have their zero degree line along the equator, an actual physical feature. Today, the prime meridian is located in Greenwich, England, but this primary reference line of longitude has not always been at its current location. Different people and cultures used different primary reference lines throughout history. ┬ĀFor example, in the second century B.C., the Canary Islands were bisected by the prime meridian because these islands were believed to be the western extent of the world. By the 1800s, maps used leading national observatories (e.g., Greenwich observatory in England), a countryŌĆÖs most prominent maritime port or city (e.g., Philadelphia in the United States), or a religious site (e.g., Jerusalem or Saint Petersburg) to determine their 0o longitude marker.┬Ā

┬Ā

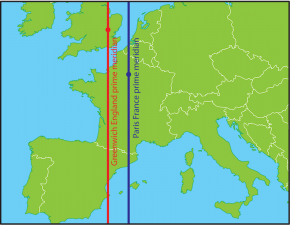

SF Fig. 1.11. The Paris Meridian is a median line (shown in blue) that ran through the Paris Observatory in Paris, France. Paris cartographers used it as the prime meridian for more than 200 years, but today the standard Greenwich Meridian (shown in red) is used.

As international travel rapidly increased in the 19th century, there was a strong need for a standardized global map system. In 1884, an international conference composed of 25 nations and states, including the United States and the independent Kingdom of HawaiŌĆśi, voted for the Greenwich Meridian to be the prime meridian for the earth. One of the reasons for this choice was that Britain had been the dominant colonial and seafaring power in the eighteen and nineteen centuries, thus their nautical maps, with Greenwich as the prime meridian, were already being used around the world. France abstained from the vote and clung to its rival Paris meridian for another 30 years (see SF Fig. 1.11). ┬Ā

┬Ā

Time Zones

┬Ā

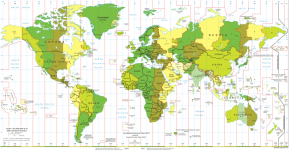

SF Fig. 1.12. On this standard time zone map of the world, areas located along similar longitude lines that are the same color have the same time.

Image courtesy of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Factbook

A day is composed of 24 hours. Thus, it might seem that dividing the earth into 24 time zones would be as simple as dividing 360┬░ by 24 to determine that the time should change by an hour with every 15┬░ of longitude. However, political and geographical boundaries, as well as convenience, have resulted in time zones that are anything but regular (SF Fig. 1.12). For example, India, Iran, Afghanistan, Burma, Newfoundland, Venezuela, the Marquesas, and parts of Australia use half-hour deviations from standard time. Other nations, such as Nepal, use quarter-hour deviations. This means that there are approximately 40 time zones rather than 24.

┬Ā

At the other extreme, some large countries, such as China and India, use a single time zone to simplify government management even though their boundaries extend far beyond 15┬░ of longitude. Before switching to one time zone in 1949, China encompassed five time zones. Since China has gone to a single time zone, neighboring countries that used to be on the same time zone are now hours apart. For example, in crossing the border from China to Afghanistan there is a three and a half hour time gain! In fact, because time zones do not follow neatly along lines of longitude, there are many places where three or more time zones meet.

┬Ā

Daylight saving time further confuses the issue of time zones because some areas observe a summertime ritual of setting their clocks an hour ahead while others, especially areas close to the equator where sunset does not change as much over the year, do not adjust their clocks for the seasons. For example, neither HawaiŌĆśi nor Arizona observe daylight savings time, but most of the contiguous United States does, including the Navajo reservation located within Arizona.┬Ā

┬Ā

Both the location of the prime meridian and the current time zone boundaries demonstrate how meridians are changeable over time as they are adjusted to political realities and the needs of society.

┬Ā