Surfing the Waves

Clarification Statement: Examples of models could include diagrams, analogies, and physical models using wire to illustrate the wavelength and amplitude of waves.

Assessment Boundary: Assessment does not include interference effects, electromagnetic waves, non-periodic waves, or quantitative models of amplitude and wavelength.

What is a Wave?

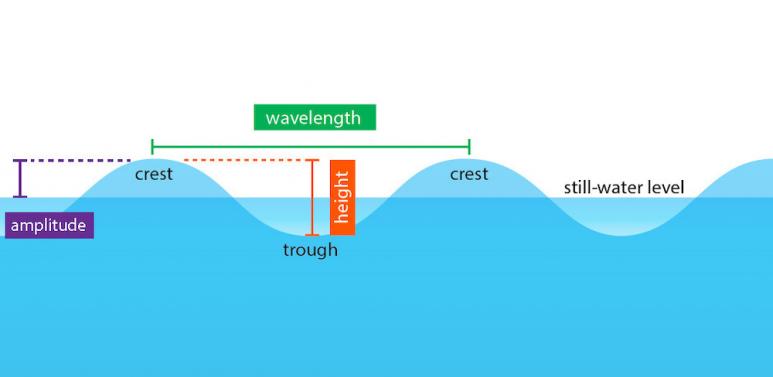

Waves are a repeating pattern of motion that transfers energy from place to place without overall displacement of matter. Mechanical waves are disturbances in any medium or substance—including water, sound, and light. Water waves happen in puddles, pools, lakes and the ocean. All waves have some features in common (Fig. 1):

- The trough is the lowest point, or bottom, between two waves.

- The crest is the highest point, or top, of the wave.

- The wave height is the distance from trough to crest.

- Amplitude is half of the wave height; it is the distance from crest to the still-water level.

- Wavelength is the measurement from crest to crest, or spacing between wave peaks).

- Frequency is the number of waves that pass a fixed point in a given amount of time.

Simple waves have repeating patterns of wavelength, frequency, and amplitude.

Fig. 1. Profile of a standing wave, or waves that do not appear to move forward or advance in position but instead they oscillate or vibrate in place.

Image by Byron Inouye, adapted by Emily Sesno

Deep Ocean Waves

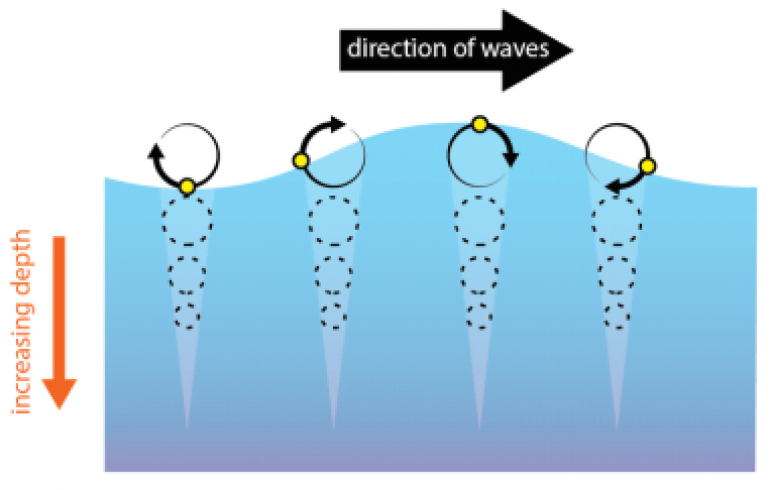

Waves can be made in water by disturbances or vibrations at the surface. Most ocean waves are caused by wind. When waves move across the surface of deep water, the water goes up and down in place. Although wave energy moves, there is no net motion of water in the direction of the wave. In actuality, as the energy of a wave passes through water, the energy sets water particles into orbital motion (Fig. 2).

By watching a buoy anchored outside a wave zone, you can see how water moves in a series of waves. The passing swells do not move the buoy toward shore; instead, the waves move the buoy in a circular fashion, first up and forward, then down, and finally back to a place near the original position. Neither the buoy nor the water advances toward shore.

Fig. 2. When energy in a wave passes through the water, water molecules move in a circular motion. Here, a small floating object (yellow circle) returns to its original location due to the orbital motion of waves in deep water.

Image by Byron Inouye from Exploring Our Fluid Earth

Fig. 3. This buoy bobs in the water outside of Honolulu, HawaiК»i, collecting data on the weather and sea conditions.

Image courtesy of NOAA NDBC

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) National Weather Service (NWS) uses buoys to track wind, air temperature and pressure, sea temperature, and wave height and frequency. The National Data Buoy Center (NDBC) maintains the network of 90 buoys around the world like the one in Figure 3.

Shallow Water Waves

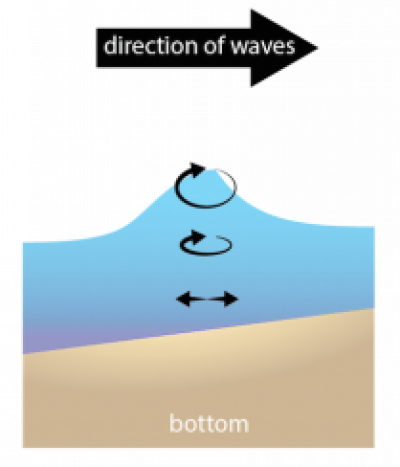

Fig. 4. As deep-water waves approach shore and become shallow-water waves, circular motion is distorted as interaction with the bottom occurs.

Image by Byron Inouye via Exploring Our Fluid Earth

When a wave passes from deep water into shallow water, the wave begins to interacts with the seafloor and changes into a breaking wave, or breaker. The energy of the wave touches the ocean floor, causing the water particles to drag along the bottom and flatten their orbit (Fig. 4). Because of the friction of the deeper part of the wave with particles on the bottom, the top of the wave begins to move faster than the deeper parts of the wave. When this happens, the front surface of the wave gradually becomes steeper than the back surface. In essence, the amplitude increases (wave gets higher) and the wavelength decreases (waves are closer together), eventually leading to a breaking wave.

In some ways a breaking wave is similar to what happens when a person trips and falls. As a person walks normally, their feet and head are traveling forward at the same rate. If their foot catches on the ground, then the bottom part of their body is slowed by friction, while the top part continues at a faster speed (see Fig. 4.19). If the person’s foot continues to lag far behind their upper body, the angle of their body will change and they will topple over.

Breaking Waves

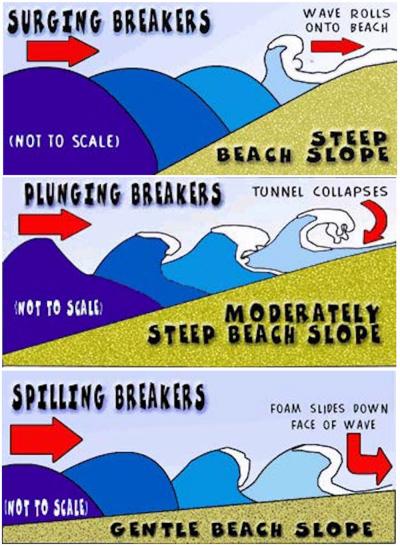

Fig. 5. A surging breaker occurs with low steepness waves and/or steep beach profiles. A plunging breaker occurs on a moderately steep beach slope and the wave crest curls over and collapses suddenly. A spilling breaker is a steep wave that occurs on a gentle beach slope when the unstable top of the wave spills down the front of the wave.

Image courtesy of original SEA curriculum

The slope of a beach affects how waves will break. The steeper the bottom slope, the greater the increase in wave height (Fig. 5). Surging breakers form when large waves suddenly hit bottom in shallow water. Surging waves break right on the the shore. Plunging breakers form where there is a moderately steep, sloping bottom. Plunging waves form barrels that cascade water in a circular motion and collapse with a forceful crash, rapidly releasing energy. Air trapped inside the barrel of the wave may spit out of the barrel as the wave races along. Spilling breakers form when the bottom slopes gradually, and fast-moving water at the top of a wave slides down the face of the wave. Spilling waves advance to shore with a line of foam tumbling steadily down the front of the wave face. Unlike plunging waves, spilling waves break slowly over considerable distances.

Surfing the Waves

Fig. 6. A surfer catches a wave at the Banzai Pipeline on the North Shore of OК»ahu.

Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Wave size increases as wind blows harder, for longer time, and over larger area. Because of this, wave patterns tend to change with seasonal wind patterns. For example, during the winter when North Pacific storms are active, waves on the northern shores of the Hawaiian Islands can be very large (Fig. 6). The Southern shores, on the other hand, tend to have their biggest waves during the summer when seasonal storms form in the Southern Hemisphere.

Swells, Tides, and Winds

Fig. 7. Ocean swells in wave sets outside Lyttelton Harbour, New Zealand.

Image courtesy of Phillip Capper, Flickr

When a surfer wants to head out to the lineup, there are many factors they want to know. They will monitor current conditions of swells, tides, and wind. When considering swells, surfers may look at swell direction, swell period, and swell height. Swells with both long periods and high heights bring large, powerful waves. For example, the 2011 "code red" swell in Tahiti was 15 ft at 20 seconds. The first 100 ft wave ridden on record was in 2013 in Nazare, Portugal, during a 30 ft, 17 second swell.

Tides are waves caused by the gravity of the moon and sun. Tides cause water levels in the ocean and lakes to rise and fall on a regular, predictable basis, covering shores during high tide and exposing them during low tide. Tides can dramatically affect the quality of surf because they influence both water motion and the relative depth of the bottom contour. For example, a small swell on a high tide at a surf break that is in deeper water probably won’t be breaking. But, that same small swell on a low tide probably would be breaking. Likewise, a big swell on a shallow reef might close out and be dangerous, whereas a big swell on a deeper reef would be probably be a lot of fun for an experienced surfer.

Fig. 8. These wind surfers off MolokaК»i must pay particular attention to wind conditions as it influences their speed and wave conditions.

Image courtesy of Alden Cornell, via Flickr

Local winds are also important when considering surf locations. Locations with offshore or side-shore wind are usually preferable to on-shore winds. This is because offshore winds help to hold the face of the wave open, to provide a smooth, surfable surface. The strength of wind also matters. Strong winds can whip water off the tops of the waves, making them harder to surf. Winds can also blow the surfer across the water, making it harder for the surfer to stay in the best position to catch the waves.

Check out this Magic Seeweed article: CHASING NUMBERS: WHEN WAS THE BIGGEST SWELL EVER?