James Harbottle Hakuʻole: The Youngest Hawaiian Youth Abroad

Na Joy Nuʻuhiwa

In 1882, James Harbottle Hakuʻole and Isaac Hakuʻole Harbottle, sons of Charlotte Naha Harbottle and Jack Pamaiaulu Hakuʻole of Kīpahulu, Maui, were sent to Tokyo, Japan as a part of Kalākaua’s program to educate Hawaiian youths abroad.

Young students in San Francisco on their way to Japan and China in 1882, accompanied by John Kapena. Seated left to right: John Lota Kaulukou, James Hakuʻole, and John Kapena. Standing left to right: unidentified man, Isaac Harbottle, and (most likely) James Kapaʻa.

This program was funded by the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Department of Foreign Affairs, and created to train future Hawaiian leaders (Quigg 1988). Similarly, it has been argued that this program was built on the foundation of Hawaiian international diplomacy, a robust Hawaiian secondary education system, and a long genealogy of Hawaiian huaka’i (Balutski 2025).

In 2025, I, Joy Nu’uhiwa, a great-great-granddaughter of James Harbottle Haku’ole, embarked on a similar journey as a part of the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa (UHM) Native Hawaiian Student Services’ (NHSS) Hawaiian Youths Abroad Program.

Although a large portion of our trip to Iāpana was to retrace the footsteps of our mōʻī in his kaʻapuni honua, my personal kuleana led me to find and follow in the footsteps of my kūpuna, Isaac and James. I was able to visit the Gakushuin University archives, the newly opened Gakushuin University museum, Imperial Household archives, and the former site of Gakushuin University in Kanda-Nishikicho. Here, I found some school records and context as to what school mightʻve been like for the boys. Before going any further, I should also mention my personal pilina to Iāpana—my mother is from Japan, and raised me speaking Japanese. Over the summers, I would also attend elementary school every year, allowing me to understand Japanese culture on a deep level.

Before the youth arrive in Iāpana, Walter Murray Gibson, Hawaiian Minister of Foreign Affairs, appoints Robert Walker Irwin, Hawaiʻiʻs Consul in Japan, as the Hakuʻole-Harbottle brothers’ guardian in Japan (Quigg 1988).

Soon after arriving, in December of 1882, Irwin reports to Gibson in a letter that he has rented a small house for the brothers, immersing them in Japanese culture through the language, clothing, and food. He notes that once they are able to speak decently, he plans to place them in a public school, which we know to be Arima Elementary. (Quigg 1988) In 1883, Irwin reports to Gibson in a letter that the brothers now attend the Nobles School, and are becoming even more proficient in Japanese language and traditions (Quigg 1988).

This is a pillar commemorating the Gakushuin Kanda-Nishikicho campus that James and Isaac attended. It was destroyed in a fire that happened during their time there, and they spent their last year in the engineering building of Tokyo University, as did all Gakushuin students.

On June 18, 1883, the Gakushuin Kanjikyoku (auditor/inspector’s office; supervisory board) journal records a man named John Kapena from Honolulu, in the Hawaiian Kingdom, requesting that two young boys by the names of Isaac and James enter the school. The entry log for the day notes that they will take an entrance exam that will identify what grade level they should enter.

「幹事局にっき」明治16(1883)年

On June 21, 1883, the Kanjikyoku (auditor/inspector’s office; supervisory board) journal records that Isaac and James took their exams. James was placed in the modern-day equivalent of the lower elementary grades, while Isaac was placed in the modern-day equivalent of the upper elementary grades.

「幹事局にっき」明治16(1883)年

Their names are also found in the Gakushuin Nyugaku-meibo (admissions guide), recorded as new students in June of 1883.

「入学名導 明治10〜45年」明治16年(1883)6月

When going to the Gakushuin and Hawaii State Archives, I have found, as other scholars have as well, that the brothers’ archival footprint is incredibly light—there are no journals, no letters, no school assignments written by the boys, anything that would indicate what they might have felt or done while in Japan. At the Gakushuin Archives, I learned that most school records from the Meiji era were destroyed in various ways, including a fire that destroyed the former Kanda-Nishikicho campus in 1886, the fires caused by the great Tokyo earthquake of 1923, and the air raids of 1945 that burned down most of the Gakushuin school grounds and buildings. The materials I was able to see today were preserved by chance, having nearly missed being burned.

Although I was unable to get a sense of what they learned or how they progressed in school, upon going to the Gakushuin museum, I was able to find a few clues as to what they might have been seeing and wearing at the time. The Gakushuin University museum main exhibit featured a diagram of the uniforms worn by students at the time, starting in 1879.

Cool uniforms. They look similar to modern-day gakuran, or military-style uniforms worn by middle school boys today.

The main exhibit also featured a ランドセル (Randoseru), a backpack commonly used by Japanese schoolchildren today. The caption notes that in 1885, students at Gakushuin started wearing Randoseru backpacks.

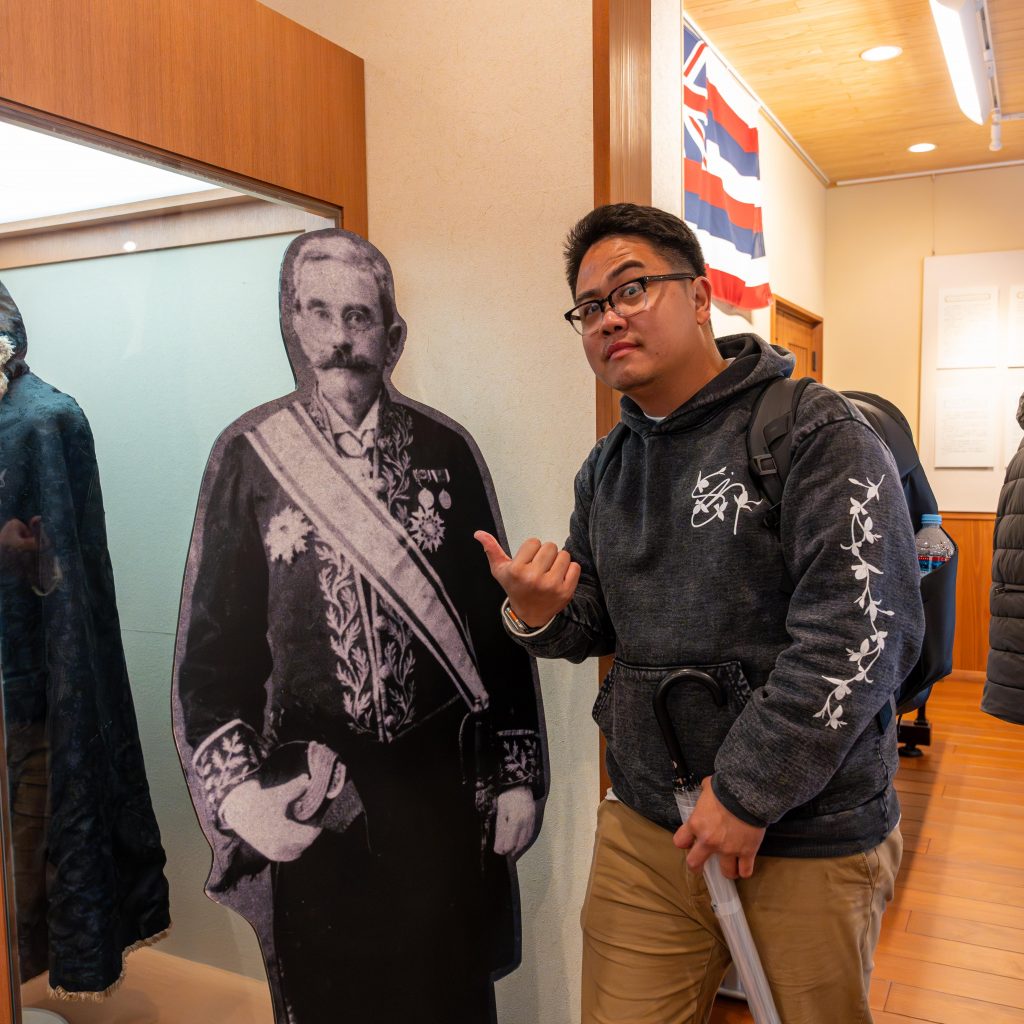

The museum featured the Prince’s randoseru from 1885. Here is a similar picture of me in 2012, wearing a light blue randoseru as I went to public elementary school in Japan.

This experience at Gakushuin struck me a little harder than I expected—here I was, a physical manifestation of Japanese and Hawaiian culture, stringing together the pieces of how my kūpuna were the same. What kanji did they learn in school that I learned too? What did they think of the randoseru? How did they survive the snow in their small uniforms, as I struggled to walk through the snow today in my 4 layers and umbrella?

Similar to how I would enter the Japanese public school system in June and leave before the Japanese school year was over, the Harbottle-Haku’ole brothers were unfortunately unable to finish their schooling in Japan.

In February of 1887, Irwin writes a communique, recommending to Kalākaua that the brothers be placed in the Imperial Japanese Military University and the Imperial Japanese Naval College, as they were now 15 and 16 (Quigg 1988). On June 30th of the same year, a rebellion led by anti-monarchists caused Walter M. Gibson to be stripped of his position, and the Bayonet Constitution to be signed under duress. Subsequently, all funding was stripped from the study abroad program, and the Hawaiian youths were called home immediately (Quigg 1988).

Sure enough, the Gakushuin Kyomu-ka (educational affairs division) journal notes that on November 22nd 1887, Isaac and James submit requests to rescind their admission.

「教務課日記」明治20(1887)年

In the Gakushuin Taigakumeibo (Admissions withdrawal list), James and Isaac are listed to have withdrawn their admission on November 24th, 1887.

「退学名簿 明治11−45年」明治20(1887)年

Once they return home, it seems like they hit the ground running—James has a successful career as a Hawaiian and Japanese language court interpreter across almost every court in Hawaii. He also had four children with Lucia Kahai Hakuʻole, one of whom is my great-grandmother. He was also a long-time member of Kawaiahaʻo Church, serving as a deacon for the last years of his life before he is unfortunately killed in an automobile accident in 1937.

James’ grave that our cohort visited before leaving to Iāpana

Isaac and his wife’s graves that our cohort visited before leaving to Iāpana

Participating in this program has given me the incredible opportunity to engage with my kūpuna and (partial) motherland in a way that is completely unique to my experience and yet, at times, very similar to what I imagine James and Isaac mightʻve felt. While my time in the program may be soon coming to an end, this is only the beginning to what I hope is a long path of scholarship ahead of me. I intend to continue this research for the sake of my ʻohana and for my kūpunaʻs story to be told in the right way, responsibly and ethically. E ola ka ʻohana Hakuʻole, e ola ka ʻohana Harbottle, e ola mau ka ʻohana Hakuʻole-Harbottle.

**all Japanese to English translations are my own and very rough.

References

Quigg, Agnes (1988). “Kalakaua’s Hawaiian Studies Abroad Program”. The Hawaiian Journal of History. 22. Honolulu: Hawaiian Historical Society: 170–208. hdl:10524/103 – via eVols at University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

Introducing Robert W. Irwin: The Hawaiian Kingdomʻs Minister to Japan

Na Kale Kanaeholo (Graduate Student, History)

It is difficult to discuss the impact of Japanese immigration to Hawaiʻi without investigating three key players: Mōʻī David Kalākaua, the Japanese themselves, and Robert Walker Irwin–of no relation to the late, great environmentalist Steve Irwin. While much historical discussion has leaned on the first two contributors, little attention has been paid to the champion of Japanese immigration to Hawaiʻi. But what does a haole man from Denmark have to do with Hawaiʻi and, relatedly, the Hawaiian Youths Abroad program established by Kalākaua?

Robert Walker Irwin in Tokyo, 1884. Courtesy Hawaiʻi State Archives.

Robert Walker Irwin (1844-1925) served Mōʻī Kalākaua and the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi in various government positions in Japan, eventually working his way up to Resident Minister in Japan and special agent of the Bureau of Immigration in 1884. He was born in Copenhagen, Denmark to William W. Irwin and Sophia Arabella Bache, the great-granddaughter of Benjamin Franklin.

While serving as the Kingdom’s minister to Japan, Irwin maintained a unique diplomatic status. To be sure, the Kingdom empowered Irwin to negotiate the terms of the Convention of 1886, which spearheaded the influx of Japanese laborers to Hawaiʻi.

A more interesting letter Irwin wrote back to the Kingdom detailed the grievance process should a Japanese laborer feel that they were subjected to harsh mistreatment while working on the sugar plantations. This was an important remedy to concerns raised during the first few years of Japanese immigration to Hawaiʻi in 1866.

Irwin also personally addressed Mōʻī Kalākaua most notably with the awarding of royal distinctions. In a letter dated March 6, 1886, Irwin submitted five individuals’ names to Mōʻī Kalākaua for royal orders and venerated status: Taro Ando (Grand Officer), George Nacayama (Knight Commander), Viscount Torii Tadafumi (Knight Commander), Toshiro Fujita (Knight Companion), and Kakechiro Nakayama (Knight Companion).

Irwin married Takechi Iki (1857-1940) on March 15, 1882. Their union was the first legal marriage between an American and Japanese citizen; the union was arranged by Inoue Kaoru, who served as the Japanese Foreign Minister at the time.

As historian Gary Okihiro reminds us, Japanese immigration to Hawaiʻi did not spontaneously emerge from Irwin’s actions alone. Years of negotiations and back-and-forth diplomacy between the two nations eventually led to the significant wave of Japanese immigration in the mid-1880s. In fact, Japanese immigration to Hawaiʻi began about two decades prior in 1866 when then-Hawaiian Kingdom Consul to Japan Eugene Miller Van Reed (1835-1873) first began contracting Japanese nationals to Hawaiʻi. The initial group of Japanese laborers, composed of 142 men and 6 women, were known as the Gannenmono, meaning “people of the first year (of the Meiji period).” However, their mistreatment at the hands of plantation owners led to a two-decade embargo on more Japanese laborers to Hawaiʻi.

In 1891, Irwin purchased a summer home in Ikaho where we are writing from today! The summer home is reflective of both the era and the city in which it stands. In fact, Irwin’s house is located adjacent to the Ikahoguchi station, which functioned as a checkpoint for those wishing to enter or leave the Ikaho area. Our visit to Irwin’s hale was marked by a healthy blanket of snow and an even healthier amount of history. The nearby museum held some of the Irwins’ belongings and included a Japanese newspaper article commemorating Mōʻī Kalākaua’s travels through Japan—even so far as including a picture of the king!

Irwin’s summer home in Ikaho, Gunma. Photo courtesy of the author.

Two sake cups with gold hae Hawaiʻi inlays. Photo courtesy of the author.

Irwin and his wife lived in Tokyo until his death in 1925, a day after his 81st birthday. He is buried in Aoyama Cemetery in Tokyo alongside his wife, who died in 1940.

References

Primary Sources:

Irwin, Robert Walker. Letter to William Lowthian Green, March 17, 1881. Hawaiʻi State Archives.

Irwin, Robert Walker. “The Japanese Minister for Foreign Affairs to Mr. Irwin.” In British & Foreign State Papers, edited by Augustus H. Oakes and Willoughby Maycock, 86 (1893-1894):1185–86. London: Harrison and Sons, 1899.

Secondary Sources:

https://discovernikkei.org/en/journal/series/robert-walker-irwin

https://immigrationtounitedstates.org/599-immigration-convention-of-1886.html

https://samurai-archives.com/wiki/Robert_Walker_Irwin

https://photoguide.jp/txt/Robert_Walker_Irwin

Conroy, Hilary. The Japanese Frontier in Hawaii, 1868-1898. New York: Arno Press, 1978.

Jung, Moon-Ho. Coolies and Cane: Race, Labor, and Sugar in the Age of Emancipation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009.

Odo, Franklin, and Kazuko Sinoto, eds. A Pictorial History of the Japanese in Hawaiʻi, 1885-1924. Honolulu: Hawaiʻi Immigrant Heritage Preservation Center, Department of Anthropology, Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, 1985.

Okihiro, Gary Y. “Chapter 5: Hawaiʻi.” In American History Unbound: Asians and Pacific Islanders, 117–49. Oakland: University of California Press, 2015.

_____. Cane Fires: The Anti-Japanese Movement in Hawaii, 1865-1945. Asian American History and Culture Series. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991.

Van Sant, John E. Pacific Pioneers: Japanese Journeys to America and Hawaii, 1850-80. The Asian American Experience. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000.

Yamada, Toru T. “Irwin, Robert Walker (1844-1925).” In Asian American History and Culture: An Encyclopedia, edited by Huping Ling and Allan W. Austin, One-Two: 418. London: Routledge, 2015. ProQuest.