Kanikau: Songs for the Soul and Inoa Hoʻopilipili

Asia Kilinoe H. Kimura

Hawaiian Language and Hawaiian Studies

It is no surprise when I make a statement saying that the people of Hawaii love their land. This is evident in the mele and oli written by our kūpuna as they were skilled poetic composers. Mele and oli were forms of expressions that refer to the love they had for the places they lived, places they resided in, the places that they visited and most importantly about other people through the referencing of these places. Examples of such expressions are shown in so many writings that we have access to through the Hawaiian newspapers. Reading old Hawaiian newspapers at the Papakilo database has helped me to get a glimpse into life through the eyes of our kūpuna. Mele did not always name a place specifically but instead, the places were written about through the use of inoa hoʻopilipili or epithets. Inoa hoʻopilipili are used profusely throughout many different genres of mele, many of which can be found in the mele and oli can be found in the Hawaiian newspapers.

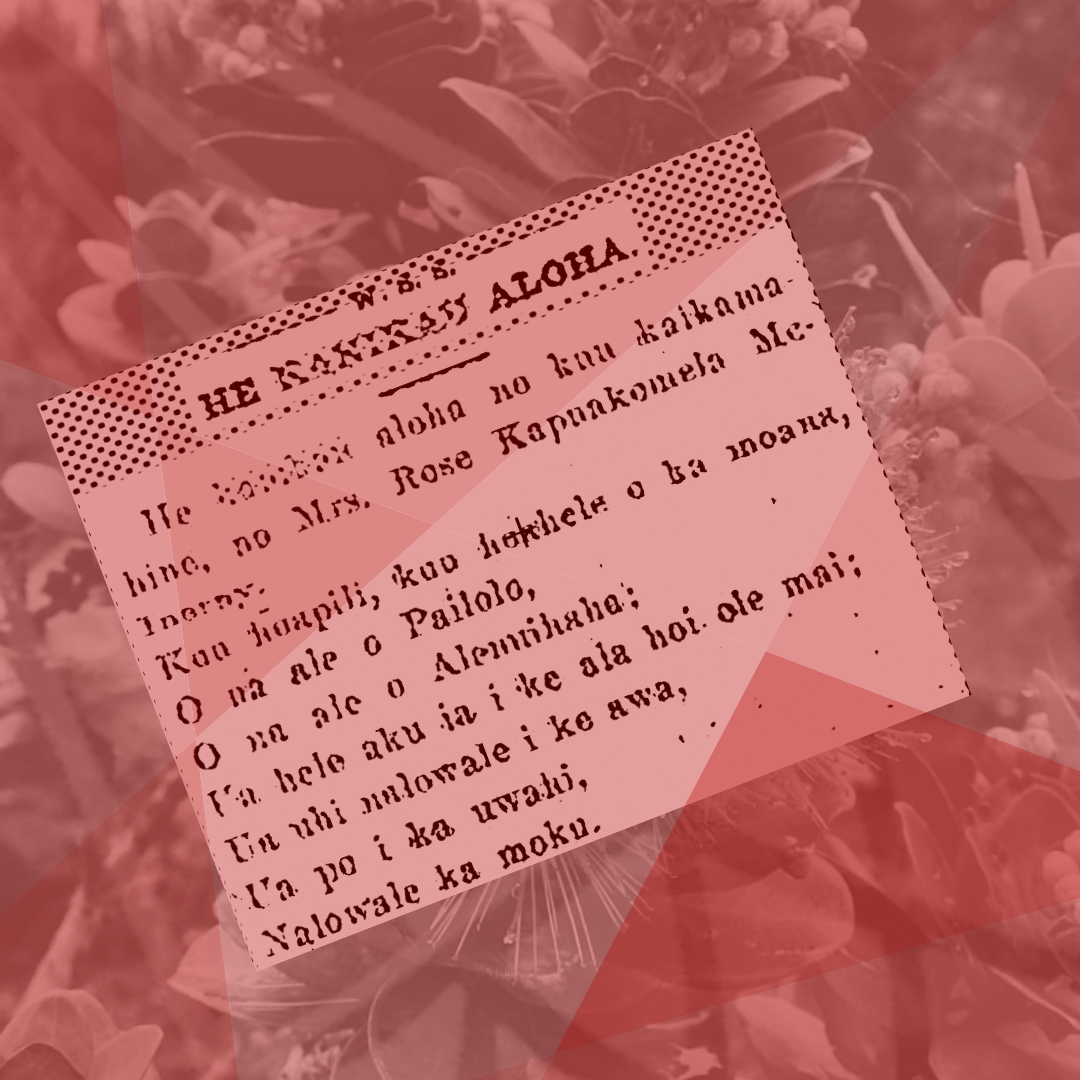

One specific genre that I have read and researched is lamentation songs or kanikau. My mentor, Noelani Arista shared with me that kanikau are songs or stories written for loved ones who have passed away. Kanikau may have told of their lives and of the composer’s love for their deceased loved one. While researching kanikau published in the newspaper between 1860 – 1869, I was able to learn a little more about how our ancestors mourned and dealt with the loss of loved ones through the expression of this specific genre of mele. I learned that in the past, kanikau were given orally and not written down. Later, kūpuna wanted to document their mele by sending them into the newspaper to be published for all to see. There were actually too many people sending in their compositions to be published in the newspaper so they began to charge people for it.[1] There was an article that said the newspaper would not just publish anyone’s composition if they aren’t of a higher social status.[2] Kanikau has helped us to learn about our kūpuna and the writers who are honoring them. This type of mele would allow the composer, the deceased, and those hearing it to share one last moment of intimacy as it would allow them to grieve in the way necessary in order for them to slowly recover and heal.

As I went through different kanikau in the newspaper, I started making notes of different inoa hoʻopilipili. I noticed that I was seeing these references quite often so I created a spreadsheet to keep track of the various phrases I came across when reading through kanikau. I use the links from the papakilo database of the different phrases found in the kanikau so that I could go through each mele line by line. I then took note of the date of when the newspaper was published (“Helu o ka lā” column), what island the inoa hoʻopilipili takes place on (“Mokupuni” column), the land name that it mentions (ʻĀina” column), the inoa hoʻopilipili, the link to the article in papakilo (“Lou” column), and any notes that I haven (“Noka” column). I usually include if there are multiple places called by the same name and list the other places so others reading it will be able to follow along easily. In the figure below, you will see in the “Mokupuni” column that there is a highlighted cell with the same name and list the other places so others reading it will be able to follow along easily. You will also see in the “Mokupuni” column that there is a highlighted cell which for me indicates something is unsure about the information and I need to go back to review it when I get more information.

I started to see trends of inoa hoʻopilipili that speak of specific places in our Hawaiian islands. There were poetic phrases that allowed the reader to visualize the place they were written for and over time have become known phrases or inoa hoʻopilipili that are automatically associated with the area of the island. Inoa hoʻopilipili may be seen as ʻōlelo noʻeau, and we will see a lot of examples that overlap with that. However, in the context of kanikau which are written to share love and grief, what do these inoa hoʻopilipili tell us about Hawaiian ways of mourning and how does it speak to the connection that we as kanaka have with our ʻāina?

Follow me on a short journey through excerpts of inoa hoʻopilipili via kanikau that you may have heard before as well as other phrases that you may not have realized were place references. My research has taken me all over the islands and even places around the world, however, let us begin with this beautiful island of Oʻahu, specifically the land right below Nuʻuanu called Kekele.

“hala ʻala o Kekele”

“mai ka ua kahiko hala o Kekele”

“aloha ka hala ʻala o Kekele”

“mai ka hala hoʻi o Kekele”

One story about this special place tells about a man named Kaulu who was a kupa from this place and who had taken a wife whose name was Kekele. Her favorite plants were hala, maile,ʻieʻie and she slept with a lei hala every night till it dried out. When the lei hala finally dried out, Kaulu planted it and from there grew the hala trees known from this land area called Kekele. Today, we have come to associate this area with the beautiful hala trees told of in this story. I came across a couple references to the area of Kekele in three different kanikau. One example of an inoa hoʻopilipili referring to Kekele says the “hala ala o Kekele” (the fragrant hala of Kekele).[3] Another example says, “mai ka ua kahiko hala o Kekele” (from the rain that drenches the hala of Kekele).[4] A few more examples of inoa hoʻopilipili say, “aloha ka hala o Kekele” (adored is the hala of Kekele), “mai ka hala hoi o Kekele” (indeed from the hala of Kekele). Although these are just a few examples of how our kupuna wrote, there are many more. They refer to areas by the scents, the scenery and the climates of the area. As you drive through the area of Nu’uanu Pali it is said that the fragrances of the hala can be smelt even though the hala grove was plowed over. Perhaps, there is a play on words here with the word “hala”? The composer understood there was a dual meaning here to this word, meaning, to pass on. Just like the fragrance of the hala that is said to linger at Kekele despite the fact that the hala grove no longer physically stands there today, it reminds us of a memory that once was. Like the haku mele of old, we see that “kaona” or the underlying meaning of things come with a level of understanding and not only do we see this practice of haku mele being used in love but in grievance as well. In this example in particular, this line shares the “wehi” or the beauty of the language, the “ʻala” in particular speaks of the fragrance of the hala which then triggers memories of the beloved deceased. Therefore, when the kanikau is published, it is published with the idea of layered meaning, that being, the moʻolelo, the memories, and the ʻāina itself all entwined together in this lei of words for a loved one.

“kuʻu kaikamahine mai ka ua kanilehua”

“ka ua kanilehua o ka nahele”

“e nana ana i ka ua kanilehua”

Our next stop on our journey through the islands brings us to a more common inoa hoʻopilipili from Hilo known as the land of the “ua kanilehua.” The story of this rain name refers to the birds that feed from these lehua. It was said, when everything was calm and still, the birds were joyous because they ate their fill of the nectar that resides within these lehua blossoms. However, when these raindrops poured down in torrent, the birds would be alarmed because the rain would pelt away the nectar and leave the birds crying.[5] The description of this rain continues to explain the description of this rain as if it was thrown down from above, “treading the bud of the ʻōhiʻa, and its blossoms, a pelting lehua rain of Panaʻewa”.[6] This inoa hoʻopilipili is used when speaking of Hilo. The land grows abundantly in the moku of Hilo because of the great amount of rain that falls throughout the year. Hilo has become famous due to the frequency of rainfall. One example from a kanikau in the newspapers says “kuʻu kaikamahine mai ka ua kanilehua” (my beloved girl from the kanilehua rain).[7] Another reference I found says, “ka ua kanilehua o ka nahele” (the kanilehua rain of the forest).[8] A third reference of inoa hoʻopilipili says “e nana ana i ka ua kanilehua” (watching the kanilehua rain).[9] As we see here, inoa hoʻopilipili can be as simple as describing the land by the name of the rain that falls or the wind that blows here. Knowing these things will allow us to have personal appreciation for the places around us. Like Elbert states, rain is a poetic expression of grief.[10] Perhaps, the haku mele was trying to showcase the great deal of emotion that they felt during this time and compared their sorrows to the pelting rain that falls in expression of love and sadness for the loss of a loved one.

“kuu wahine mai ke one kani o Nohili”

“Hoohihi koʻu manaʻo i ke one kani o Nohili”

“o ka auhau ke one o Nohili i ka pali”

“kupinai ke kaha ke one o Nohili”

Next, I will take you along to the island of the “barking sands,” Nōhili on the island of Kauaʻi. Here, this place is known for its massive sand dunes. A few examples I found of the usage of this inoa hoʻopilipili in the newspaper says “kuu wahine mai ke one kani o Nohili” (my beloved women of the barking sands of Nohili),[11] “Hoohihi koʻu manaʻo i ke one kani o Nohili” (My thoughts are entangled by the barking sand of Nohili,[12] “o ka auhau ke one o Nohili i ka pali” (the sand of Nohili is the bark that grows abundantly on the cliffs),[13] “kupinai ke kaha ke one o Nohili” (the hot, dry, sand of Nohili is mourned).[14] These particular lines are well known because they are seen in several genres of songs. The inoa hoʻopilipili that our kūpuna use gives us visual imagery of the land even if we may never have a chance to visit them in person. For this inoa hoʻopilipili in particular, we know that Nohili is referred to as an ancestral place and through these ancestral places can we connect these words and associate our loved ones to. We often talk of the ʻāina and of characteristics that make it special but most times we do this, we also associate these thoughts and feelings to someone through the referencing of these ʻāina. Thus, this is just a way we situate those who have passed on, even if they no longer exist physically in our realm of the living there are still references to places that bring back memories and thoughts of these people as if they were still here with us. Therefore, when one hears the kani of the sands of Nōhili, one may recall the kani of precious moments spent there with those who have passed on. Knowing these inoa hoʻopilipili gives us a different capacity of the way we view our land. A lot of inoa hoʻopilipili are seen in songs of lament, love songs, aloha ʻāina songs, and other genres. If we learn these inoa hoʻopilipili and the story behind each one, the capacity of our ability to understand our language and tell our stories in our native tongue will help us in our thinking and understanding. Kanikau has shown me that the way our kūpuna grieved and honored the deceased is unique. Kanikau gives us a direct visual of how they expressed themselves in these times. It is a way for us to get to know the loved one that has passed as it usually speaks of the person’s life and places they loved.

It is important for us to learn the land references that our kūpuna used. Learning the inoa hoʻopilipili referred to by our kupuna can be considered a form of true aloha ʻāina. This will help us to reclaim our spaces and native thought about them. Knowing the names of the land you grew up on is something that our kūpuna knew so firmly. It strengthens our foundation of being Hawaiians in Hawaiʻi and also gives respect to those of the past by letting their names live beyond our own mouths.

Our kūpuna were smart, strong and brilliant. Kanikau shows us “snapshots” into the lives of our kūpuna. They knew that their language was important, and our land was important. Having documented kanikau in the newspapers provides our generation with knowledge of the way our kūpuna expressed themselves during the time of hardship and loss. Doing the research seems to be becoming a regular thing for the modern-day Hawaiian because it is necessary for us to relearn the things that made our kūpuna exceptional in composing mele that exemplified the way they loved and grieved. Our love is intimately tied to the land for the land helps us express our love and loss. These newspapers provide us with a way to understand our own culture from another time. Afterall, all this knowledge is a privilege to have so we should use every opportunity we can to honor them by learning all that we can.

Asia Kilinoe H. Kimura

Asia Kilinoe H. Kimura

I was raised here in Oʻahu in Mōʻiliʻili just below our Mānoa campus. I am currently in my third year here but technically have the class standing of Senior pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in Hawaiian Language and Hawaiian Studies.

Why is research important for Native Hawaiians?

Research is important because it allows us to tap into the knowledge of our kūpuna. Many things that we know today is from doing research. Our kūpuna left us multitudes of documents that have yet to be reviewed and understood, we owe it to them to learn all they can to continue their efforts of restoring and revitalizing our language and culture.

What is one thing you’ve learned from your project?

Kanikau has shown me that the way our kūpuna grieved and honored the deceased is unique. Mele kanikau gives us a direct visual of how they expressed themselves in more ways than one during these times specific times of grievance and mourning. Knowing these inoa hoʻopilipili gives us a different capacity of the way we view our land. A lot of inoa hoʻopilipili are seen in songs of lament, love songs, aloha ʻāina songs, and other genres. If we learn these inoa hoʻopilipili and the story behind each one, the capacity of our ability to understand our language and tell our stories in our native tongue will help us in our thinking and understanding.

Citations:

Akana-Gooch, Collette L., et al. Hānau Ka Ua: Hawaiian Rain Names, p. 51. Kamehameha Publishing, 2015.

Kalionui, J. W.. “He kanikau NO ESETERA WAHAHEE.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 31 Mei 1862.

Kapaalua, Helene. “He Kanikau no Nehemia Hepa.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 27 Kēkēmapa 1862.

Kealakaa, A. B. W.. “He Kanikau Aloha no S. Luka.” Ka Hoku o ka Pakipika, 26 Kepakemapa 1861.

Kekai, N.. “He Kanikau no J. Kapena Apiki.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 24 ʻOkakopa 1863.

Konaaihele. “He Kanikau.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 19 ʻApelila 1862.

Kuhaupio, D.. “He Kanikau no ke emi ana o ka Lahui Hawaii.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 6 Iulai 1865.

“Na Palapala no ka Hae.” Ka Hae Hawaii, 8 August 1860.

Mrs. Naale. “Kanikau aloha no Iulia Kahaule.” Hoku o ka Pakipika, 28 August 1862.

Mrs. Kaleialoha, O. “Ka make ana o Lonoliʻi.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 2 January 1864.

P., J.. “Kanikau aloha no Mrs. Maleka Ii. Kamealoha nuiia i make aku la.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 1 Nowemapa 1861.

“Ancestral Visions of Aina (Land That Feeds).” AVAKonohiki.org, www.avakonohiki.org/.

Sterling, Elspeth P., and Catherine C. Summers. Sites of Oahu. Bishop Museum Press, 1993.

[1] In conversation with Noelani Arista.

[2] “Na Palapala no ka Hae.” Ka Hae Hawaii, 8 August 1860.

[3] A. B. W. Kealakaa. “He Kanikau Aloha no S. Luka.” Ka Hoku o ka Pakipika, 26 Kepakemapa 1861.

[4] Konaaihele. “He Kanikau.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 19 ʻApelila 1862.

[5] Akana-Gooch, Collette L., et al. Hānau Ka Ua: Hawaiian Rain Names, p. 51. Kamehameha Publishing, 2015.

[6] Ibid. p. 61

[7] J. P.. “Kanikau aloha no Mrs. Maleka Ii. Kamealoha nuiia i make aku la.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 1 Nowemapa 1861. Ke kuhi nei wau, ʻo J. P. ʻo ia nō ʻo John Papa ʻĪʻī.

[8] Mrs. Naale. “Kanikau aloha no Iulia Kahaule.” Hoku o ka Pakipika, 28 August 1862.

[9] Mrs. O. Kaleialoha. “Ka make ana o Lonoliʻi.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 2 January 1864.

[10] Elbert, Samuel Hoyt. Symbolism in Hawaiian poetry. p. 392.

[11] J. W. Kalionui. “He kanikau NO ESETERA WAHAHEE.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 31 Mei 1862.

[12] Helene Kapaalua. “He Kanikau no Nehemia Hepa.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 27 Kēkēmapa 1862.

[13] N Kekai. “He Kanikau no J. Kapena Apiki.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 24 ʻOkakopa 1863.

[14] D. Kuhaupio. “He Kanikau no ke emi ana o ka Lahui Hawaii.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 6 Iulai 1865.