Na Kaimana Kawaha, Graduate Student, ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi

As the third days approaches us here in London, England, we as kanaka far away from our one hānau continue to feel the ʻeha of not being on Maunakea physically standing in solidarity with our Lāhui for more than just the safety of our sacred mauna, but for our essence and existence as a people. We each encountered different hihia over the past three days, believing somehow that we are not supposed to be here on this huakaʻi. However, we were reassured by two profound scholars and kiaʻi, Dr. Jamaica Heolimeleikalani Osorio & Kaleikoa Kāʻeo, who sent messages specifically for our group that our presence here in London is more than necessary and needed as we continue to spread the word and utter the name of our sacred mauna across the globe, giving her mana to stand and protect us as we reciprocally continue to do for her. Our mauna conversations led me to think of a mele aloha ʻāina that speaks of the beauty of Kona, Hawaiʻi, the one hānau of one of our beloved Hawaiian Youths Abroad scholars, Joseph Aio Arthur Kamauoha. As individuals, we all have many kuleana to ʻauamo, and sharing the story of Mr. Joseph Kamauoha is one that is long over-due. Our kuleana to Maunakea, however, is not individual at all, but rather a collective kuleana that is carried together upon the backs of our Lāhui. With that, I share this mele, “Kaulana nā Kona,” to start this blog in hopes that we can see and feel the unbreakable and intangible relationship between kanaka and ʻāina, more specifically though, their mauna. I leave these lyrics to this mele aloha ʻāina below to remind us that when we think of our fellow kanaka, we think of them not as an individual, but by what caressed and raised them, that being our ʻāina.

Kaulana nā Kona

Na: Alice Aiu Kū

Kaulana nā Kona i ke kuahiwi

Kū Hulālai kau mai i luna

No luna ke ʻala aʻo ka maile

Lau liʻiliʻi e moani nei

Huli aku Hulālai iā Kawaihae

I ke kai hāwanawana

Nānā iā Kailua, Keauhou, Nāpoʻopoʻo

Hoʻokena, Hoʻōpūloa, nā awa kaulana

Lana aʻe ka manaʻo o ia Kona

I ke kai māʻokiʻoki

Haʻina mai ka puana i ke kuahiwi

Kū Hualālai i kai malino aʻo Kona[1]

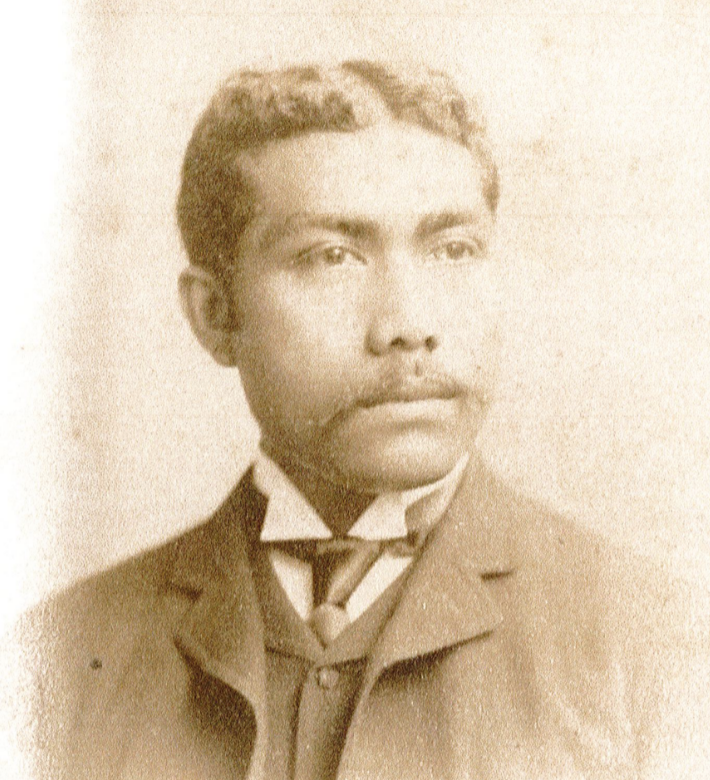

Joseph Aio Arthur Kamauoha[2] was born in 1861 in Nāpoʻopoʻo, Kona, Hawaiʻi. His genealogy traces back to the time of Kamehameha I, where one of his kūpuna, Panila, was the kahuna kālai waʻa to the Naʻi Aupuni, essentially bringing his ʻohana closer to governmental power. He was a student at both ʻIolani and Punahou School, two prestigious schools created during the Kingdom era.[3] He attended the latter right before being hand-picked to be part of the second cohort of students that participated in King Kalākaua’s “Hawaii Youths Abroad” program.[4] He, along with two other boys, Matthew Makalua and Abraham Piʻianaiʻa, were sent with Colonel Judd to England in 1882, Kamauoha would attend King’s College, while the other two would attend St. Chad’s.[5]

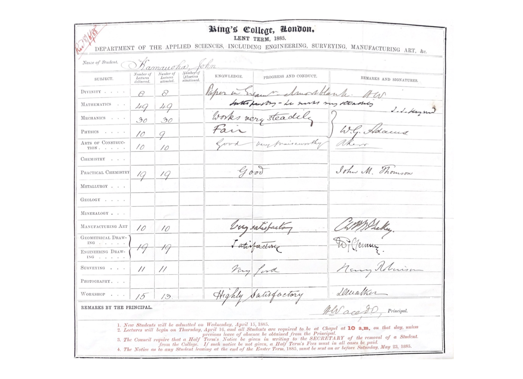

There at King’s college, Kamauoha was a fine and remarkable student with exceptional grades receiving more than satisfactory level scores in courses like workshop, surveying, and mechanics.[6] He enrolled in a vast range of courses at King’s College such as chemistry, mathematics, divinity, and even surveying, exemplifying the rigorous education he had endured. In his letter, Manley Hopkins, the Hawaiian Consul General in London who became the guardian of the three young men, wrote that, “Kamauoha is prudent, studious, diligent: gives no ground for complaint in anyway, but is rather dull in conversation: indeed speaks but little.”[7] After a few years spent in London, Kamauoha finds an interest in engineering and even considers it to be the field he wants to finish his studies in.

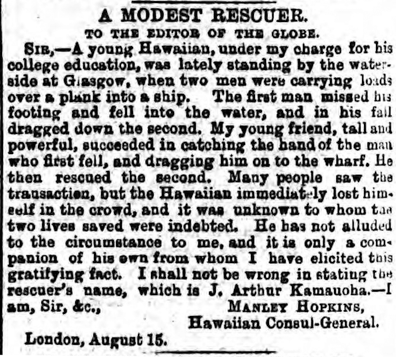

It is evident that Kamauoha was more than just a bright student, but a well-oriented, mannered, and ethical gentleman. In an English newspaper article published in 1884, Kamauoha saves two men from drowning along the waterside of Glasgow. Manley writes in the article, “Many people saw the transaction, but the Hawaiian immediately lost himself in the crowd, and it was unknown to whom the two lives saved were indebted.” This quote is evident of his humility and kind soul that made up Kamauoha.

In early 1885, Kamauoha requests permission to study under an apprenticeship in his letter to the King of Hawaiʻi. Kalākaua responds and allows him to do so under the theoretical course in order for him to truly learn the ways of this type of engineering. Kalākaua also states in his letter that he is not to come home until he has learned all that is needed in the apprenticeship for that is the purpose of these young men being sent abroad.[8] The schools terms were paid for so he could begin to study engineering.

In October of the same year, however, Joseph Kamauoha was faced with declining health. Hopkins write in his letters to Gibson of some of the medical issues he is faced with. He goes on to say, “he had had trouble with one hand requiring a slight operation, and that a chill had accesioned inflammation in his eye.”[9] He had been sent to Torquay to recover by his guardian, Hopkins, to do get better in the “Frying-pan of London” in which he did. His trip to Torquay, however, led to his death on March 26th 1886.[10]

His death had left Hawaiʻi and its people with grieving hearts for the brave young man who had studied abroad. Newspapers, such as Ka Nupepa Elele and Ko Hawaii Pae Aina, published articles regarding his death. One goes on to say, “Aloha wale ia kama nana e hookaulana la i ke kulana o Hawaii // Beloved is this child who had made Hawaiʻi’s stature renowned.”[11] In the letter written by his good friend Matthew Makalua and published in newspaper The Pacific Commercial, Makalua says, “Kamauoha was a great favorite with all who enjoyed his friendship and acquaintance, and his loss will be greatly felt by them all.” [12]

As we prepared to leave London for Torquay today, we were anxious and ready to visit the grave of a national hero that had been so long forgotten. We caught a three and a half hour train ride from London to Torquay where we sat and made lei to adorn the grave at which he laid. After stopping at the train station, we immediately headed toward the cemetery. Nālani led the way as we wandered the walk-ways looking for what had been captured in the picture that ʻAnakala Hardy Spoehr gave to us. I caught a glimpse of a faded Hawaiian flag left on an illegible grave and immediately yelled out, “I think this is it!” We all rushed over and sure enough, the landscape matched the picture Hardy gave us. We were stoked to have found the grave of one of Hawaiʻi’s own in an foreign land, but saddened that his name was not engraved on it. Kamauoha is buried on top of other individuals due to the cost of the funeral and planning arrangements done by Mr. Manley Hopkins.

Before we started the lei chants and adoring the grave, I sung the song, “Kaulana nā Kona,” to honor him and his one hānau, Nāpoʻopoʻo, Kona. I hoped that the words I sung were taken into a deeper understanding that “Kaulana nā Kona i ke kuahiwi” doesn’t just mean “Famous are the Konas because of its mountain,” but that these “Konas are famous because of Kamauoha for he is his mountain.” That he doesn’t just stand like a normal man but like the kuahiwi Hualālai, tall and proud protecting his ʻāina and people. I hoped that when I sang, “kau mai i luna,” it didn’t just show the height of the Hulālai, but of how honored and esteemed he is to us for the work that he had done for the Lāhui. I hoped that when I sang “Nānā iā Kailua, Keauhou, Nāpoʻopoʻo, Hoʻokena, Hoʻōpūloa,” it didn’t just mean to simply look at these very famous places along the Kona coast, but that we care, cherish, and pay attention to these places because that is aloha ʻāina ʻoiaʻiʻo. And Kamauoha did so in hoping to return home to better our Kingdom with the ʻike that he had learned. I hoped that when the words “Lana aʻe ka manaʻo o ia Kona i ke kai māʻokiʻoki” were sung that we thought about how many times Kamauoha must of wondered and longed to go back to his home famous for its choppy seas but never being able to even until this day. I hoped that this mele showed more that just a love for our ʻāina, but a love for the people of that specific ‘āina. I hoped that we can honor him with this mele so that the stories of Kona and the story of Kamauoha continue on.

[1] Kīhei de Silva. “Kaulana Nā Kona” Article. 2014

[2] No diacritial marks are used in the spelling of his name as told to me by family members

[3] ʻIolani Admissions Archives

[4] “Nuhou Kuloko” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa. 25 June 1881

[5] State Archives Tuition Receipts

[6] State Archives Course Reports at King’s College

[7] Manley Hopkins, letter to Walter Murray Gibson, 22 Jan. 1885, HY A.

[8] King Kalākaua, letter to J. A. Kāmauʻoha, 15 June. 1885

[9] Manley Hopkins, letter to Walter Murray Gibson, 12 Oct. 1885, HY A.

[10] Manley Hopkins, letter to Walter Murray Gibson, 27 Mar. 1886, HYA.

[11] “Waiho Na Iwi I Na Aina Malihini” Ka Nupepa Elele, 24 Apr., 1886.

[12] “Death of Mr. J. A. Kamauoha” The Pacific Commercial, 03 May 1886