No Nā Makani

As described in Mānoa 2025: Our Kuleana to Hawaiʻi and the World Strategic Plan 2015-2025, aloha ‘āina is a necessary guiding kuleana for the university. But what is aloha ʻāina? There is no singular definition–in fact, we recognize that there are many different facets and dimensions to this deeply-rooted value and practice. In the 2025 strategic plan, aloha ʻāina is described as a “recognition, commitment, and practice sustaining the ea – or breath – between people and our natural environments that resulted in nearly 100 generations of sustainable care for Hawaiʻi.” Most importantly it explains that our collective kuleana as a university involves acknowledging and listening to the “guidance from Native Hawaiian ancestral knowledge and wisdom.”

As we continue to pule for our ʻohana in Maui, we consider some of the sentiments expressed as plans are made to “rebuild” Lāhainā. Solutions abound for how to prevent another tragedy. But there are some who believe that only modern solutions hold the key. Specifically, that the use of traditional indigenous knowledge is irrelevant to this discussion: “climate change has wreaked havoc here, which means solutions of the past aren’t viable now.” (link) This rejection of ancestral knowledge is regrettable.

While we cannot always change hearts or minds, we can bring the past forward and (re)introduce it to all of you. One of the ways we can show our care and respect for Lāhainā and our Maui ʻohana is by learning everything we can about this beautiful ʻāina.

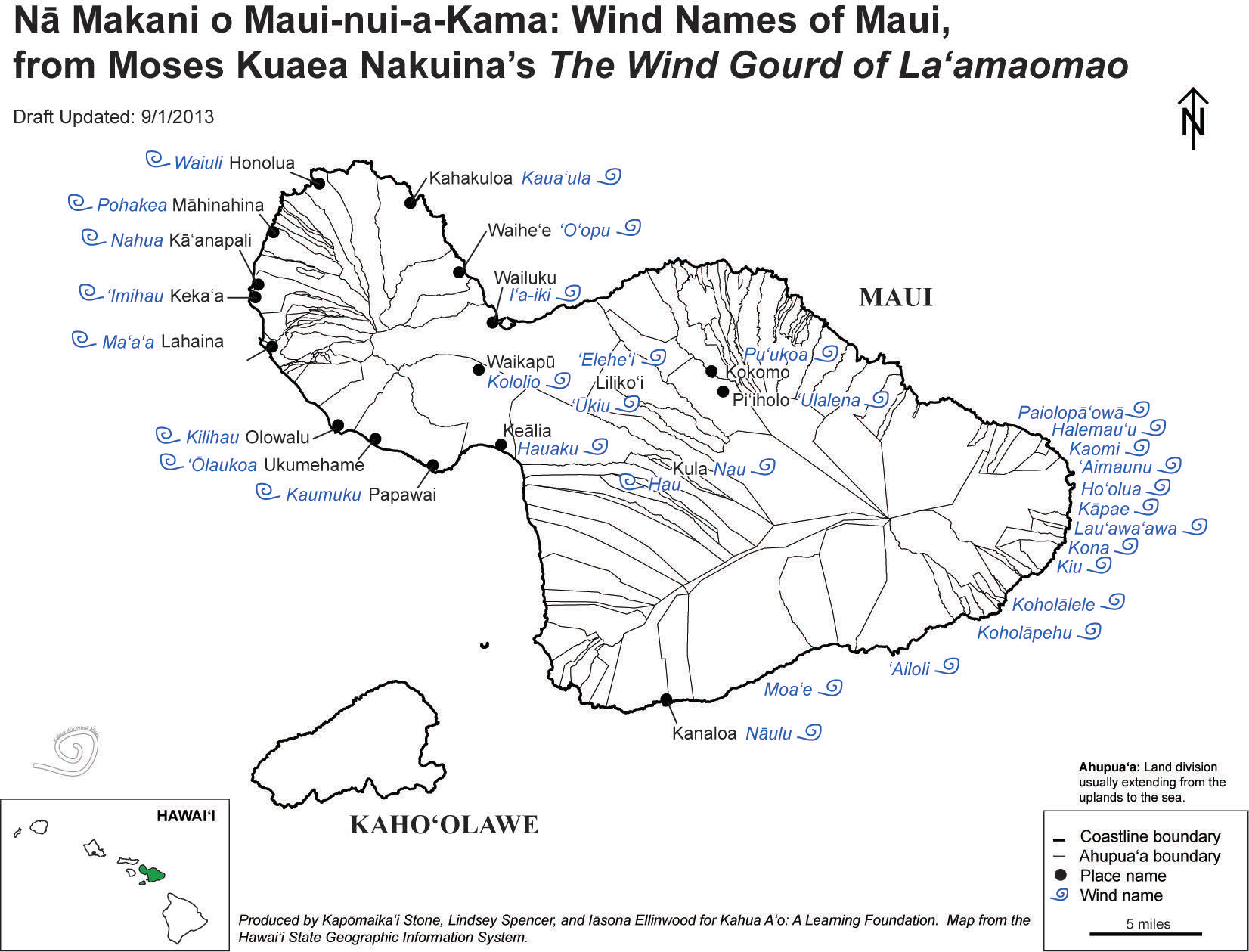

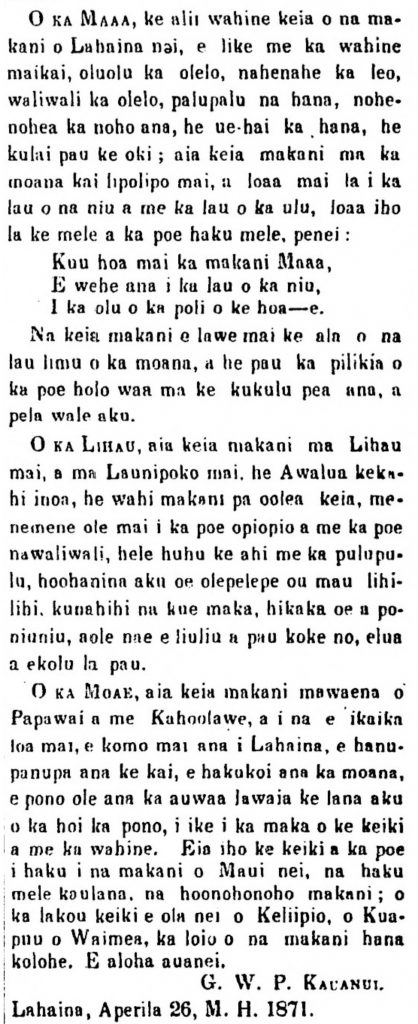

In this post, we guide you to an article written in 1871 by G.W.P. Kauanui about the winds in west Maui. According to Collette Leimomi Akana, author of “Hānau Ka Ua: Hawaiian Rain Names,” the Hawaiian language has over 600 words and terms that exist to describe wind. Matthew Dekneef, “Hawaiians Have More than 200 Words for Rain,” Hawaiʻi Magazine (March 4, 2016) (link). These words are vividly used to distinguish Hawaiʻi’s winds in myriad ways: temperature, duration, intensity, location, direction, etc. The great number of names reflects the deep connection between Native Hawaiians and our environment. It is also a reminder that our ancestors were keen observers of nature. These observations were carefully and extensively recorded during the 19th century in Hawaiian language newspapers. These articles are not just “relics of the past”–they have the potential to provide access to an extensive repository of historical data.

It is our hope that you find the beauty in learning about Lāhainā from our kūpuna. If you want to learn the pule and oli to help support Maui, please visit this link.

CONCERNING THE WINDS

The usual winds of Lele [Lāhainā]: The Kaomi, a wind between Molokaʻi and Lahaina. If this wind is extremely strong, then there will be a great deal of rain in Kāʻanapali, drenching it, and ʻAkamu and Nāhaku will shiver; then it is called the Nahua wind. The wind that is strong at the mountain is the Hoʻolua, and if it is terribly cold, then it is the Kiu wind. If the winds are cold and carry litter, dust, and leaves from the forest, hats of travelers, and floor mats from houses, then it is a Pāʻāhiohio wind. Another name is Akua Lapu, and Moe Lepo is another name.

THE KAUAʻULA, this is a strong wind. This is the father of the winds in Lahaina. This wind is directly upland. However, this wind warns of its wrath ahead of time, because for three days it roars against the mountain, persisting against the mountain and blowing here and there. When the residents of Lahaina hear the roar, they tie down buildings, fastening them securely to the earth, and put properly fitted braces. When this wind comes, it is dreadful to see. There is a great deal of dust, there is a great deal of litter, it roars through the leaves and flattens the shrubs, large trees are dislodged, and Lānaʻi disappears in the dust. The birds of the uplands, the ʻiʻiwi, ʻapapane and so forth, are torn away by this wind, leaving their offspring and nests.

THE MAʻAʻA, this is the chiefess of the winds here in Lahaina. Like a fine woman, the talk is pleasant, the voice is soft, the words are smooth, the actions are tender, the presence is lovely, the action is swaying, and at the end one is knocked over. This wind comes from the deep blue ocean, and is found among the fronds of the coconut tree and the leaves of the breadfruit tree, and the song of the composers is received, to wit:

My beloved friend from the Maʻaʻa wind,

Spreading the fronds of the coconut,

Like the comfort of the bosom of the friend.

This wind brings the scent of the seaweed of the ocean, and ends any problems the people sailing on canoes had with setting up sails, and so forth.

THE LĪHAU, this wind comes from Līhau and from Launiupoko. The Awalua is another name. This wind blows roughly, with no compassion for the young and the feeble. The fire and kindling blaze angrily, so you must gently shield your eyelashes, the eyebrows furl, and you stagger dizzily. It is not long, though, before it ends. Two or three days, and it ends.

THE MOAE, this wind is between Papawai and Kahoʻolawe, and if it is extremely strong, then it reaches Lahaina, making the sea choppy and agitated, and it is unsuitable for fishing fleets to stay in place. They must return, so as to see the faces of their children and wives. Here below is the son of those who named the winds of Maui, the famous composers, the wind classifiers; their living children are Keliʻipio, and Kuapuʻu of Waimea, the lawyer of the rascal winds. Greetings again soon.

W. P. KAUANUI.

Lahaina, April 26, 1871.

Citation: G.W.P. Kauanui. 1871 May 6. “Niniu Ka Malu Ulu O Lele – No Na Makani.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, Volume X, Number 18, Page 1. Retrieved from Papakilo Database, http://papakilodatabase.com. Translated by Kapomaikaʻi Stone, Iasona Ellinwood and M. Puakea Nogelmeier. Institute of Hawaiian Language Research and Translation, 2013. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi.