Sea urchins help researchers fight reef-smothering algae

University of Hawaiʻi at MānoaDoctoral Candidate, Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology/SOEST

Brian J. Neilson, (808) 227-7677

Acting Administrator, State Division of Aquatic Resources

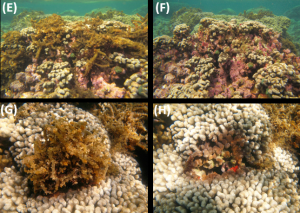

A management approach that combines manual removal and outplanting native sea urchin is effective in reducing invasive, reef-smothering macroalgae by 85 percent on a coral reef off Oʻahu, according to researchers.

Globally, the health of coral reefs is threatened due to rising ocean temperatures and ocean acidification. Local factors such as invasive macroalgae also pose a serious risk to coral reefs—monopolizing reef habitats and overgrowing and smothering native species, such as corals.

Chris Wall, a doctoral candidate at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) in the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST), state Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) Acting Administrator Brian J. Neilson and others tested a novel approach to curbing the abundance of invasive macroalgae on Kāneʻohe Bay’s coral reefs.

Divers manually removed invasive macroalgae with the assistance of an underwater vacuum system called “The Super Sucker.” Then, hatchery-raised juvenile sea urchins (the Hawaiian native collector urchin, Tripneustes gratilla) were outplanted to graze on invasive algae to control regrowth.

The team removed more than 40,000 pounds of invasive macroalgae, outplanted 99,000 sea urchins and treated nearly six acres of reef area over two years. During this period, invasive macroalgae declined in response to treatments and, more importantly, there were no observed negative effects to important reef calcifiers such as corals and crustose coralline algae.

Unfortunately, there are often limited options for reducing invasive macroalgae without causing further environmental damage. Prior to this study, scientists at UH Mānoa, DAR and the Nature Conservancy showed the manual removal/urchin herbivory method worked at reducing invasive macroalgae in the laboratory and in small enclosures on the reef.

“This management approach is the first of its kind at the reef-scale,” said Wall. “Our research shows promise as an effective means to reduce invasive macroalgae with minimal environmental impact, while also incorporating a native herbivore to regulate a noxious invasive species.”

DAR is continuing to monitor the reefs of Kāneʻohe Bay and the long-term effects of macroalgae removal and urchin herbivory on coral reefs. In addition, scientists are actively studying the influence of local weather and global climate phenomena, such as the 2014–2016 El Niño and global bleaching episodes, as drivers of changing coral and invasive macroalgae abundance through time.