Bacteria direct Hawaiian squid to create more inviting home

University of Hawaiʻi at MānoaPostdoctoral Fellow, PBRC, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology

Edward (Ned) Ruby, 608-332-5002

Professor, Pacific Biosciences Research Center, School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology

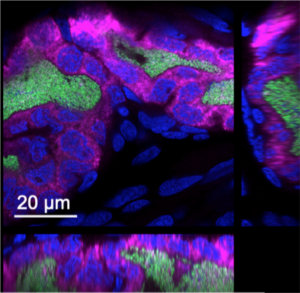

Microcopy: sRNA (pink) surrounds Vibrio (green); squid cell nuclei (blue). Credit: Moriano-Gutierrez

Bacteria living symbiotically within the Hawaiian bobtail squid can direct the host squid to change its normal gene-expression program to make a more inviting home, according to a study published in PLoS Biology by researchers at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology (SOEST).

Nearly every organism and environment hosts a collection of symbiotic microbes—a microbiome—which are an integral component of ecological and human health. In bacteria, small RNA (sRNA) is a key element influencing gene expression in the microscopic organisms, however, there has been little evidence that beneficial bacteria use these molecules to communicate with their animal hosts.

In the new study, lead author Silvia Moriano-Gutierrez, a postdoctoral fellow in the Pacific Biosciences Research Center at SOEST, and co-authors, found a specific bacterial sRNA that is typically responsible for quality control of the production of protein in the bacterium plays an essential role in the symbiosis between Vibrio fischeri and the squid.

Communicating a vital message

The Hawaiian bobtail squid recruits V. fischeri to inhabit the squid’s light-organ, as these bacteria are luminescent and camouflage the squid during its nighttime hunting.

Through RNA-sequencing, the scientists found in squid’s blood sRNA sequences that were produced by bacteria inhabiting the light-organ and found a high concentration of a specific sRNA within the host cells lining the crypts where the bacteria live.

“The presence of this particular sRNA results in ‘calming’ the immune reaction of the squid, which will increase the opportunity for the bacteria to persistently colonize the host tissue, and deliver their beneficial effects,” said Moriano-Gutierrez. “This work reveals the potential for a bacterial symbiont’s sRNAs not only to control its own activities but also to trigger critical responses that promote a peaceful partnership with its host.”

The researchers, including co-author and UH Mānoa undergraduate student Leo Wu, determined the bacteria load sRNA into their outer membrane vesicles, which are transported into the cells surrounding the symbiont population in the light organ—decreasing the squid’s antimicrobial activities in just the right location.

“It was unexpected to find a common bacterial sRNA that had evolved for a house-keeping function in the bacterium to be specifically recruited into a bacterium-host communication during the initiation of symbiosis,” said Moriano-Gutierrez.

“We anticipate that a host’s recognition and response to specific symbiont sRNAs will emerge as a major new mode of communication between bacteria and the animal tissues they inhabit,” said Moriano-Gutierrez. “Other symbiont RNAs that get into host cells remain to be explored.”